The United States reneged on its foreign aid commitments. Nepal’s malnourished children and their families are paying the price.

The Pulitzer Center's support for this reporting was made possible through the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF).

Lumbini province and Kathmandu, Nepal—Mina Jaiswal hadn’t reached her second birthday when she died in April in Kalaphanta, a village set among a patchwork of rice and wheat fields in Nepal’s western lowland plains. For the first year of her life, Mina seemed to grow normally, and played among the other children in this farming community along the border with India.

Then a few months ago, she became sick and started to lose weight, says her mother, Anita Devi Jaiswal. In March, a health worker wrapped a measuring tape around the toddler’s upper arm and recorded just 10.5 centimeters. Mina was diagnosed with severe wasting, the most visible and deadly form of malnutrition.

She was prescribed ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF)—a nutrient-rich peanut-based paste that helps severely malnourished children recover weight. But the local health post’s stocks of this potentially lifesaving treatment were empty. Her family was told to come back the following week. By early April they had received the RUTF sachets, but Mina had developed edema, a buildup of fluid associated with particularly severe wasting. “Her whole body was swollen,” Anita says. “She gave up eating and drinking.”

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Health workers said Mina should go to a specialized treatment center, more than 1 hour’s drive away. But her father says he had to work in the fields and take care of the rest of the family, including Anita, who was heavily pregnant with the family’s sixth child. “I thought that I should take her once I had given birth,” Anita says, holding her newborn baby in her lap. Mina died before they could make the trip.

Until U.S. President Donald Trump returned to office and ordered a freeze on foreign aid in January, Narainapur, the rural region that includes Kalaphanta, was one of 498 municipalities in Nepal targeted by a sweeping effort to save children like Mina. Led by the international nongovernmental organization (NGO) Helen Keller Intl, the work was funded by a $72 million award from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and was slated to run from 2024 to 2029. In March, as Mina’s health was deteriorating, Helen Keller and local partners should have been working with the government to visit households and screen children for wasting, ensure a consistent supply of RUTF, and support overworked staff at health posts across the country. They’d also planned to tackle some of the myriad factors exacerbating poor nutrition in marginalized and underserved communities like Narainapur’s, including a lack of family planning and nutritional education, as well as food insecurity.

But the project, known as USAID Integrated Nutrition, no longer exists. When it suspended foreign aid, Trump’s administration issued a stop-work order forcing the program to halt operations. A late February letter from USAID, by then largely dismantled, said some of the project’s malnutrition efforts could continue under a “limited waiver for life-saving humanitarian assistance.” Days later, a new letter informed Helen Keller that the whole project had been terminated. Like the thousands of programs canceled via similar letters, USAID Integrated Nutrition, the administration determined, was “not in the [U.S.] national interest.”

Global health experts are still working to estimate the full impact of the collapse in U.S. aid funding on worldwide efforts to fight malnutrition. Multiple reports have already linked USAID’s dismantling to deaths among malnourished children in countries experiencing hunger crises including Nigeria and Somalia, even as RUTF piles up unused in USAID warehouses.

In Nepal, long considered a success story in reducing child malnutrition, the cuts are likely to jeopardize hard-won progress. USAID’s withdrawal has already frozen hundreds of millions of dollars in government and NGO funding, ended programs in health and other sectors, and threatened thousands of aid jobs. Even critics of Nepal’s reliance on foreign aid agree there will be significant repercussions from the United States’s abrupt retreat, which comes as other international funders are also announcing aid cuts, says development anthropologist Jeevan Sharma, who co-directs the Centre for South Asian Studies at the University of Edinburgh and is studying some of the effects of USAID’s withdrawal. “Nobody’s celebrating it,” he says. Even now, “There’s a sense of shock.”

The U.S. Department of State, which is reportedly absorbing what remains of USAID, did not answer questions from Science but said in an emailed statement it is “working to ensure that our foreign assistance and our policies are appropriately aligned.” It added that it is “working with the Government of Nepal to continue to deepen our cooperation.”

As for USAID Integrated Nutrition, the program “had a direct impact on the lives of many children,” says Chandrakala Sigdel, who spent 7 years as a nutrition facilitator in Narainapur and a nearby municipality. She worries the funding cuts mean “the number of malnourished children is likely to rise, and in the long run, this could push the entire nation back into the cycle of malnutrition. … That truly upsets me.”

GLOBAL HEALTH EXPERTS have long argued that investing in child nutrition makes both humanitarian and economic sense. A lack of proper nutrition is implicated in roughly half of deaths in children under age 5. Although it’s frequently associated with war and natural disasters, it is also driven by poverty, chronic food insecurity, and poor maternal health, among other factors. Children with the most severe form of wasting, a condition called severe acute malnutrition (SAM), are more than 10 times as likely to die as well-nourished children, usually from common illnesses. SAM affects more than 12 million children, more than half of whom are in southern Asia. And about 150 million children worldwide are stunted—they’re too short for their age—typically because of chronic poor nutrition.

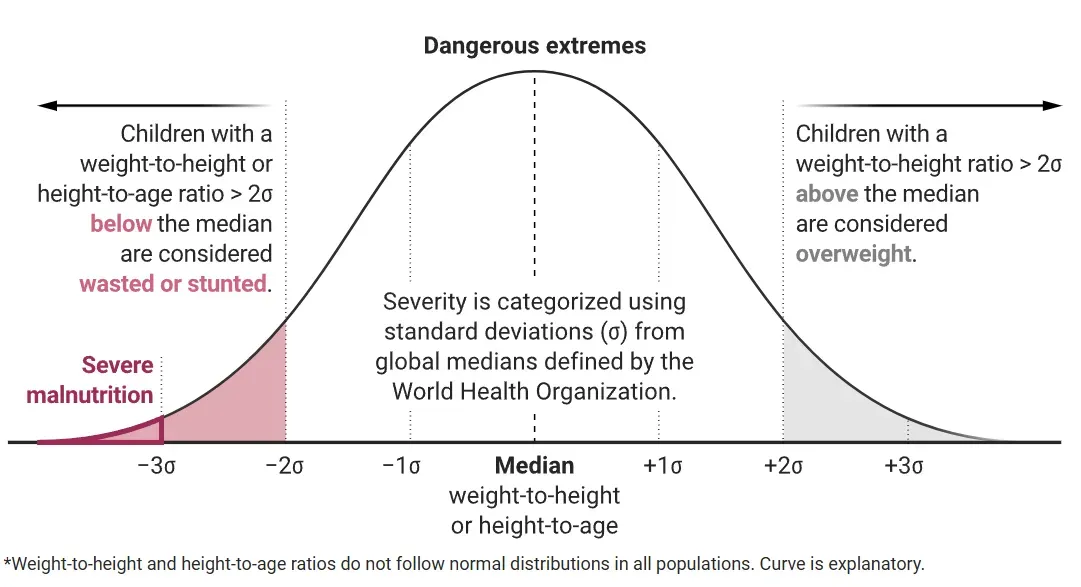

Types of malnutrition

Malnutrition in children includes multiple forms of undernutrition—wasting, stunting, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and being underweight for one’s age—as well as obesity and being overweight. Undernutrition is implicated in about half of deaths among children under age 5 worldwide.

WASTING

Low weight for height

Wasting usually reflects rapid weight loss due to illness or lack of nutritious food. Its most severe form increases a child’s risk of death 10-fold.

STUNTING

Low height for age

Stunting typically reflects chronic undernutrition, which can harm physical and neurocognitive development, and has been linked to lower educational achievement and earning potential.

Malnutrition undercuts a country’s productivity, says Saskia Osendarp, executive director of the Micronutrient Forum, which studies and advocates for improvements in nutrition. She co-authored a commentary in Nature earlier this year warning that a complete cutoff of U.S. funds to treat wasting would not only take a direct toll—she and her colleagues estimated an additional 163,500 child deaths a year—but also have serious economic consequences. People who survive malnutrition can bear lasting scars, she explains, particularly if they were affected in the critical 1000-day developmental window from conception to 2 years old. For some, “Their immune systems will be impaired, they will do less well in school, they will grow up to be adults in jobs where they earn less.”

Past U.S. administrations have viewed global nutrition funding as key to promoting resilient democracies and bolstering U.S. national security and prosperity. Since USAID’s creation in 1961, Congress has approved billions of dollars for efforts to fight wasting, stunting, and nutrient deficiencies worldwide, including in Nepal. The relationship has not always been smooth: Some critics here have decried the government’s dependence on foreign aid for health and other sectors and accused funders of undermining the country’s sovereignty, fueling corruption, and propping up neocolonial narratives.

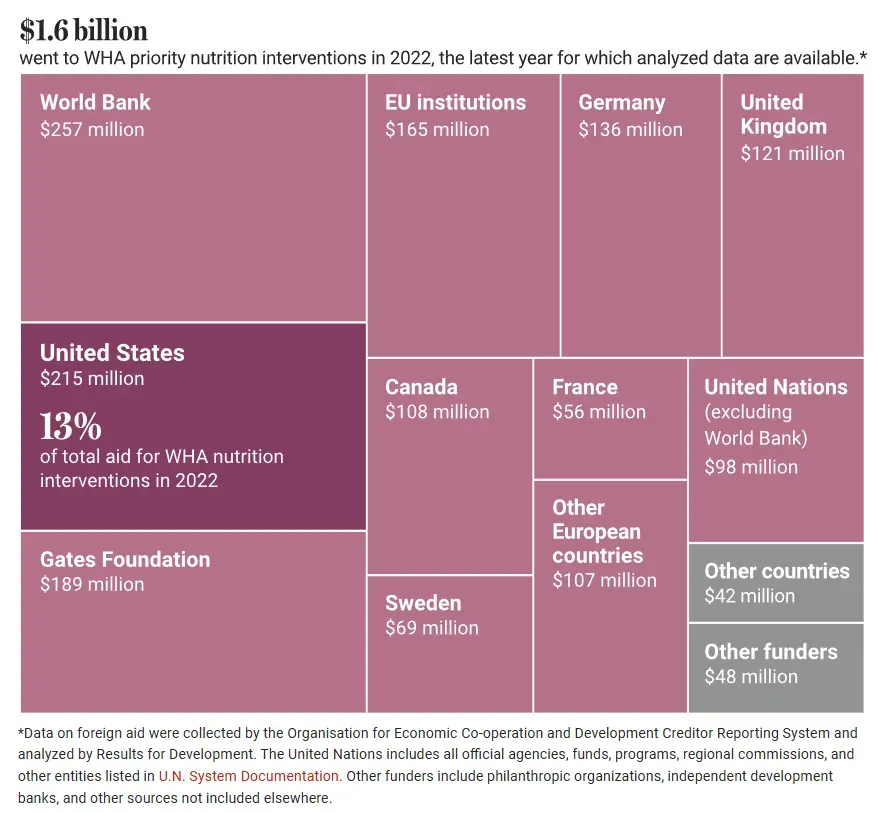

Patchwork funding

In 2022, the United States was the largest single-nation direct funder of priority nutrition interventions to meet World Health Assembly (WHA) nutrition targets. Such interventions include treatment of wasting, stunting, and anemia, and promotion of breastfeeding. Excluded are other types of nutrition-relevant funding such as boosting agriculture or providing access to clean water.

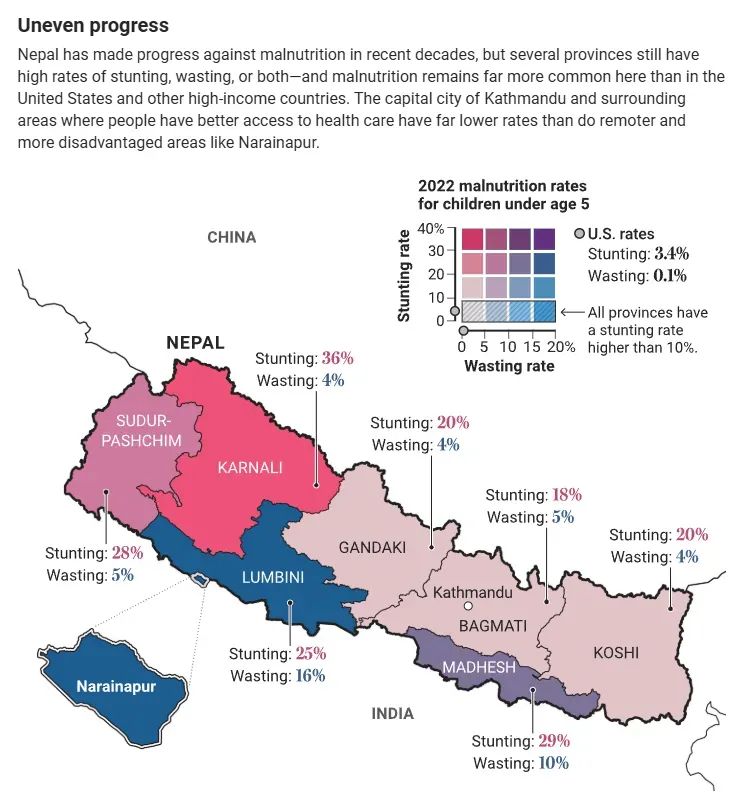

Still, when it comes to malnutrition rates, many credit aid from the U.S. and other international funders with helping turn the tide. Starting in the mid-1990s, Nepal went from having one of the highest levels of stunting in the world, at more than 60% of children under age 5 by some estimates, to less than half that by 2022. Wasting dropped in this time, too, from more than 11% to about 8%—though these figures mask substantial differences among provinces and communities (see map, below).

Nepal’s government has helped drive this progress with increasing investments in health care, while surging remittances from Nepalis abroad have lifted many families out of poverty. International funders like USAID have contributed through both direct funding and support for government- and NGO-led nutrition programs, including a highly successful vitamin A supplementation initiative launched in 1993.

In 2011, USAID began a major nutrition-focused project called Suaahara, Nepali for “good nutrition.” It ran for 5 years, and its follow-up, Suaahara II, spanned the next seven. Eventually reaching 389 municipalities in six of Nepal’s seven provinces, the programs organized community activities and public health campaigns promoting good nutrition. They also supported local, provincial, and federal governments with staff training, procurement of commodities such as RUTF, supplies of equipment, and overall health policy planning. While Nepal’s government oversees health and other programs, USAID staff on the ground have been the ones “who often facilitate and make the system actually work,” notes Sharma, who was a researcher at Tufts University, which collaborated on Suaahara I, as that program was first being implemented.

USAID Integrated Nutrition was supposed to be Suaahara’s successor. Designed in collaboration with the Nepali government, it was going to scale up the program’s efforts to all seven provinces, increase assistance for hard-to-reach communities, and gradually hand over all responsibility to local partners by the end of its 5-year run.

Uneven progress

Nepal has made progress against malnutrition in recent decades, but several provinces still have high rates of stunting, wasting, or both—and malnutrition remains far more common here than in the United States and other high-income countries. The capital city of Kathmandu and surrounding areas where people have better access to health care have far lower rates than do remoter and more disadvantaged areas like Narainapur.

The perceived U.S. commitment was so strong that people in Nepal’s government regularly spoke of “USAID” synonymously with nutritional programming, says Bhim Prasad Sakopta, chief of the health coordination division at Nepal’s Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP). When other partners showed interest in investing in Nepal’s health programs, he adds, “we would request they go to other sectors, not nutrition—because the U.S. is already doing something in nutrition.”

BEFORE THE PROJECT disintegrated, Sigdel had been one of hundreds of contracted workers across Nepal tasked with implementing the country’s integrated nutrition programming. As part of Suaahara II, she visited families’ homes alongside female community health volunteers. She measured children’s weight, height, and arm circumference; made referrals for those with wasting; and ensured treatment reached the kids who needed it. When requests for RUTF got delayed along the multistep chain from municipal health posts to regional logistics centers, she and her colleagues would use USAID’s channels to break the jam.

Sigdel says many communities “are still unaware that malnutrition is a serious issue [that] can be treated through proper nutrition and timely visits to health care centers.” She and other workers advised families on how to prevent malnutrition in the first place by preparing nutritious, varied meals including poultry and vegetables rather than unhealthy snack food, and regularly feeding children when they are sick, as conditions such as diarrhea can cause rapid weight loss.

Staff also advocated healthy spacing between births, because back-to-back pregnancies put strain on a mother’s health and in turn increase the risk of low birth weight. They promoted breastfeeding, which can be challenging for many mothers without guidance. (The World Health Organization has called breastfeeding “one of the most effective ways to ensure child health and survival,” in part because breastmilk protects babies against infections.) Other activities highlighted basic hygiene and sanitation, and how to properly introduce foods when babies reach about 6 months old. Some households in vulnerable areas also received equipment and agricultural training to try to boost production of nutritious crops.

The USAID projects’ network of committed, community-based workers like Sigdel was one of the programs’ greatest strengths, says Bibek Kumar Lal, who directs the family welfare division at MOHP and worked closely with USAID staff. “They had a very deep reach in the communities.”

Data suggest the Suaahara programs drove significant improvements in a number of metrics, including maternal underweight, infant lengths, and child diet, which got better faster in target districts than in areas that weren’t part of the program. There were also improvements in less tangible outcomes such as local governance and community health volunteers’ knowledge. The gains emerged despite a serious earthquake in 2015, a complete overhaul of Nepal’s political system the same year, and severe economic impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic, notes Edward Frongillo, who co-directs the Global Health Initiative at the University of South Carolina and led one of the evaluations.

That’s not to say Suahaara and its follow-ups didn’t face criticism: Some people were concerned the multiple interventions and wide coverage might be spreading program resources too thin, Sharma notes. The impact of more focused interventions might have been easier to measure, too.

Despite such concerns, the projects had built up a lot of goodwill over the years, says Helen Keller’s Pooja Pandey Rana, who directed both Suaahara II and USAID Integrated Nutrition. In expanding the work to new districts, the team built on the trust of communities and government staff accumulated through more than a decade of collaboration, she says. USAID Integrated Nutrition had already begun to ramp up activities in Narainapur and hundreds of other municipalities by the beginning of this year, and federal and regional governments had baked the project into their plans for the following fiscal year. “The ship was about to leave,” Lal says, “when it sank.”

As funding froze and then vanished, the team was forced to return equipment and terminate staff. Motorbikes once used to transport workers and commodities to vulnerable communities were left in a dry port on the outskirts of Kathmandu, alongside hundreds of other vehicles stranded from canceled USAID projects across the country. About 60 people from Helen Keller’s Nepal office lost their jobs; and all of USAID Integrated Nutrition’s contracted community staff were laid off—Sigdel among them.

AT THE KALAPHANTA HEALTH POST, a cluster of small buildings in a quiet goat-filled field where Mina came before she died, health workers are feeling the effects of the program’s withdrawal. Ram Sundar Yadav oversees malnutrition cases here. He says the nine staff at the post were already stretched thin implementing more than 30 government health programs, including immunization, treatment for diseases such as tuberculosis, and vitamin supplementation, for some 1400 households. Now, they are demotivated and even more overworked. Among other support, his team had counted on USAID for referrals and follow up of malnutrition cases that might otherwise be overlooked.

Radha Maurya, a 10-month-old girl from the village of Nausahara, could easily have been one of those missed cases. After Radha’s mother died just over 1 month after giving birth to her, the family bought formula just over the border in India to try to replace the breastmilk. But Radha struggled to put on weight and was so weak when she turned 8 months earlier this year that the family thought she wouldn’t survive, says her grandmother Anokha Maurya. They took Radha to various traditional healers and tried different foods and drinks, but she continued to deteriorate. “Nobody here knew anything,” Anokha says.

It wasn’t until a neighbor told the family about a child with similar symptoms and recommended a visit to the health post that they brought Radha in for screening, where she was diagnosed with SAM. Although Radha, like Mina, had to wait for RUTF to arrive, the treatment helped. Several weeks later, she can lift her head for a few seconds at a time, and the corners of her mouth sometimes curve up when her relatives smile and speak to her as she lies in her grandmother’s arms. Her father is still worried about her, and Anokha, who also helps with Radha’s older siblings, says she fears for the family once she’s gone. “I am raising them, for as long as God has given me life.”

Health workers are also concerned about aid cuts’ effects on nutrition for younger infants, who rely completely on milk. Kalpana Upadhyaya Subedi, a consultant physician at Paropakar Maternity and Women’s Hospital, had been expecting support from USAID and other funders to expand a lactation counseling program and human milk bank to other hospitals across Nepal. That plan has now been shelved, alongside numerous others supporting maternal and newborn nutrition and health.

The disruption to nutrition efforts is likely to set back nationwide improvements in child health, several experts told Science. But it will take time to quantify the fallout—and not just because malnutrition takes time to develop. The aid withdrawal could also jeopardize government surveys used to monitor child health, Lal says. “If those surveys are not conducted, we will not even know the impact,” he says. “That is the most worrying part. We’ll all be blind.”

ON THE FIRST THURSDAY of May, as Nepal celebrates Labor Day, Rana sits in her team’s stark former headquarters in Kathmandu. Less than 24 hours after the official closing of USAID Integrated Nutrition, she’s organizing the clear-out of office equipment before remaining staff downsize to a smaller space in the building.

Asked in March about the project’s termination, she told Science she had “never felt so hopeless.” Now that some of the shock has passed, she and colleagues at Helen Keller have been identifying critical activities and strategizing how to keep them going with any funds they can find. It’s challenging work: Her team is just one of many chasing a rapidly dwindling pot of aid money. “It’s not just Nepal,” Rana says. “Everywhere, this crisis is happening.”

Others are also looking for solutions. Some health officials in Lumbini province, which includes Narainapur, say they have been working to stretch government funding designated for maternal and newborn health to include malnutrition services. Officials at MOHP are trying to interest development partners they previously directed away from nutrition to now “allocate at least a few resources” to the area, and have reached out to philanthropic organizations to explore possible collaborations, Sakopta says. Back in Narainapur, Sigdel, who has since found work supporting girls’ education, says she still tries to share information about good nutrition with families she meets.

Many politicians and commentators have argued the crisis should force a rethink of how Nepal uses international money. “USAID’s abrupt exit underscores the highly fragile, aid-dependent system,” says Vibhav Pradhan, a researcher in public policy at the Institute for Integrated Development Studies in Kathmandu. The country needs to diversify its support, strengthen its governance, and build health systems that can withstand shocks like this in the future, he says. Sakopta adds that “the great lesson learned for us” is to allocate domestic rather than external resources for critical functions in health and other sectors. “Other resources, they are always uncertain. At any point ... they may stop their funding.”

The Nepali government will still be able to run other critical services such as essential vaccinations, Sakopta says, and may be able to cover some of the lost nutrition aid. The 2025–26 budget, issued at the end of the May, moderately upped funds for MOHP from about 4.6% to 4.9% of the total budget—though it’s still unclear how much malnutrition work this will be able to support.

Long term, Nepal and other countries might be able to come up with better, more efficient ways to fund health and other services, notes John Hoddinott, an economist at Cornell University who studies nutrition. “People can be creative and innovative, and maybe that’s what we’ll see in this space.”

But what frustrates many involved with terminated projects is how quickly they have been forced to adapt. With some warning, government officials and aid workers say, people could have planned and tried to mitigate the impact on human lives. Instead, as everyone scrambles to adjust, there will inevitably be families, facing situations like Mina’s and Radha’s, that “fall through the cracks,” Rana says. “In the end, it’s always the most vulnerable women and children that suffer.”

.jpg.webp?itok=SGAhTnP4)