The Israeli occupation imposes a severe toll on the Palestinians living in the West Bank. Since 1967, the occupation has controlled every aspect of Palestinian life. However, during the current Israel-Gaza war, the occupation has become more suffocating, and violence has increased dramatically. In the West Bank city of Nablus, I spoke with many Palestinian residents of the city and of the New Askar refugee camp, which took in the Palestinian refugees of the Arab-Israeli wars of 1948 and 1967. Those I spoke to are bracing for a further escalation of violence, fearing an all-out war.

“And that's where the military trucks come almost every night, and you can also see it from your room; but don’t be scared,” Nablus resident Mohammed, who preferred not to share his full name because of safety concerns, said as he stood on the balcony of his home pointing down to the street. Mohammed was talking about the nighttime raids of the nearby refugee camps by the Israeli military that have become a daily occurrence. “One time they stopped right by the house, and I was so scared, and I ran from the window, but they left eventually; so do not worry,” he said, reassuring that everything would be OK as he showed me around the house.

On my journey through the West Bank, from the Jordanian border to Nablus, I was in a state of confusion, curiously looking out the bus window. I thought to myself, I must be looking at one of the most bizarre places on Earth.

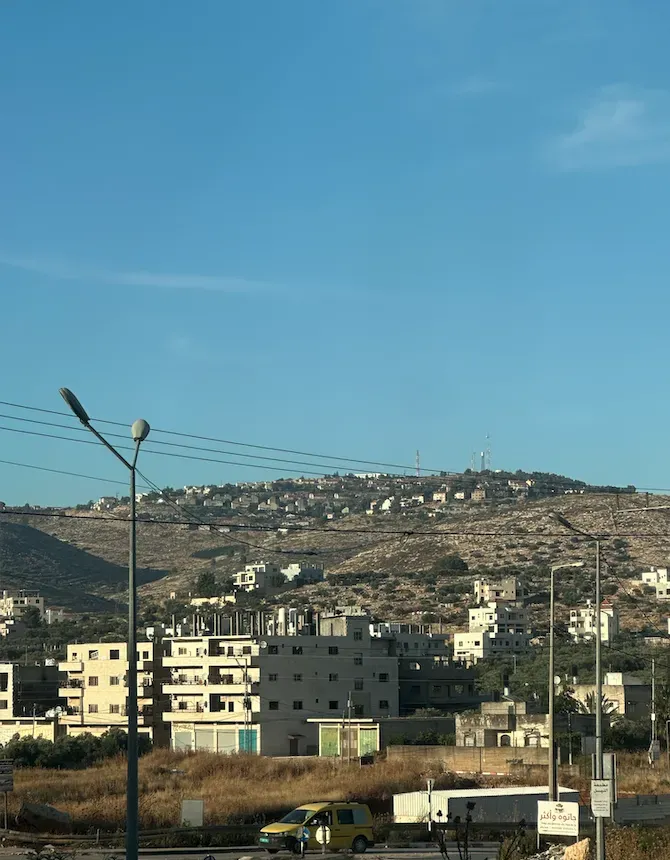

The West Bank, home to approximately 3 million Palestinians, living in cities surrounded by Israeli settlements and outposts and enclosed by a formidable separation wall, fragments the territory into a patchwork of Palestinian and Israeli areas. Driving along the highway to Nablus, I couldn't look away, I was afraid of missing any detail of this complex landscape as we drove by Palestinian towns, Israeli settlements, military posts, and farms. I had never seen anything like it in my life.

Eventually, I arrived at the checkpoint to enter Nablus, greeted by a bright red sign in English, Arabic, and Hebrew that read, “This road leads to Area ‘A’ under the Palestinian Authority. The entrance for Israeli citizens is forbidden. Dangerous to your lives and is against the Israeli law.”

After waiting to get through the checkpoint, I saw the Israeli flags and Hebrew signs that filled the landscape on the road abruptly being replaced by the Palestinian flag and Arabic.

To the people living here in the West Bank, like Mohammed, this is the status quo, the occupation, and it has been since 1967. But the status quo is changing, becoming even more unbearable for Palestinians. In the shadow of the war in Gaza, since October 7, 2023, the increased violence in the West Bank fades into the background on media outlets. Israel is always “cutting the grass,” Mohammed said when I arrived, referring to Israel's policies in the West Bank to keep resistance at bay.

Mohammed is a 21-year-old nursing student who grew up in the New Askar refugee camp. He dreams of leaving Nablus and living in Dubai, but now it is almost impossible for him to even go beyond his city limits. He drove me around to see many of the checkpoints in the city, afraid the whole time of being stopped by Israeli soldiers.

“We will go back now; it's too dangerous,” he said while approaching a checkpoint that's only five minutes from his home. “We drive slow so they think we will stop the car to shoot at him, and so they are scared.”

But the Israeli soldiers at the checkpoint are not the only ones scared by Mohammed driving his car near the checkpoint. “We are in danger now … I have a flag of Palestine on my car, on the number of my car, if they saw that, they will destroy the car,” he said.

For Mohammed, his car being destroyed is the least of his worries.

“What makes me scared is the last two videos I posted,” he said. “That's the reason I am scared to cross the checkpoint. I made a video on Instagram, Boycott for Gaza; it reached 2 million and a half. I made a video about what happened in Nour Shams camp, they killed people, they arrested many people … so they will arrest me, and they will say like, ‘This is incitement,’ that is my accusation … so this is ‘resistance’ for me.”

Under Israeli Administrative Detention Law, the state may hold prisoners indefinitely without charging them or allowing them to stand trial, a practice documented by B’Tselem, which is applied almost exclusively to Palestinians in the occupied territories. Mohammed is afraid of being arrested under this law for “incitement” in his Instagram posts, like Boycott for Gaza.

Mohammed was arrested two times when he was a teenager for illegally entering Jerusalem to pray at the Al-Aqsa Mosque during Ramadan. So, he said he would not be surprised if he were arrested again. “They (Israeli soldiers) took me, and everyone was taking picture(s) of me, and they put me on TV with the headline, ‘Oh they arrest one child from Al-Aqsa Mosque,’” he laughed as if sharing a funny anecdote and continued the story of his arrest.

“I was 17. And then,they put handcuffs, blind my eyes, and took me (away).” Mohammed paused for a moment. “And then when I arrived there was one soldier who came and put me in the bathroom and he started to say in Arabic, ‘Oh you throw a stone at us, we throw a stone at you,’ and he started to hit me.”

Asked if he threw a stone, Mohammed said, “No, I didn't. They just started to hit me here and there and I started to cry. I was a kid, but even now I would cry,” he started to laugh again, “and then they took me to jail.”

Looking out the window while driving back to his home from the checkpoints, I immediately noticed the expansive new settlement communities outside the city high in the mountains connected to the separate road for the Israeli settlers with no checkpoints. The neighboring road for Palestinians was lined with cars waiting to get through the checkpoint and out of the city, visually dividing the landscape. “You see,” Mohammed said, as he pointed to all the settlements high above the city, “everywhere … settlements.”

Talking with Mohammed on the drive, it was clear he was angry but also frightened, waiting for the whole situation in the West Bank to collapse. “No, here we have war too!” Mohammed said when asked about the escalating situation in the West Bank. “There are airstrikes … they destroyed Jenin, also Nablus Balata camp,” he said. “And there will be more war I think.”

He does not speak about the occupation with violent rage, but rather sorrow verging on defeat and disbelief. “They killed my friend in one of the raids,” he said.

Mohammed’s friend was at New Askar camp during a raid a couple of months ago. Mohammed said to his knowledge his friend was not part of any militant group. “He was throwing stones when they were storming the camp. They stormed the camp, and they shot one … they arrested another one and they killed my friend … they could have shot him in his leg, but they didn’t, they shot him (with) more than 10 bullets.”

Mohammed paused, he looked at me for a reaction, but I sat there silently, barely able to comprehend how an event like that would affect me in my life.

“I was with him one day before he died,” he said, continuing the story, pulling out his phone to show me something. “In the camp we made this for him.”

He showed a picture of a memorial for his friend with pictures and candles. “Last week, the occupation forces came, and they destroyed [the memorial].”

Walking the streets of Nablus, everywhere you look, on the streets, in the shops, on the mosques, there are pictures of resistance fighters—as the residents of Nablus referred to them—who have died. The near-daily raids are part of a large counterterrorism operation by Israel to suppress growing violent resistance groups, according to CNN. Yet the militant groups are growing in tandem with these raids, which have also killed and imprisoned many innocent civilians, including children, alongside the militants, highlighted in a report by The Washington Post.

All of it brings about an atmosphere of fear in Nablus and elsewhere in the West Bank. “It's OK, maybe they will kill me, and you will remember me,” Mohammed said, laughing.

Currently, the situation in the West Bank is escalating dramatically. The scale of death and destruction of the war in Gaza and the worsening humanitarian crisis has understandably captured the focus of world media and politics as it pertains to the region. However, suffering for Palestinians is not limited to the Gaza strip—Mohammed's experiences show that Palestinians in the West Bank face extreme conditions.

As of March 2025, 896 Palestinians have been killed in the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, since the start of the war in Gaza in October 2023, according to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), compared to 155 in 2022, which already saw the highest fatalities in the West Bank since 2005, as documented by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

As I saw while driving with Mohammed, road closures and checkpoints, as well as his fears of arrest and settler violence, keep him restricted to Nablus. While restriction on the movement of Palestinians in the West Bank is nothing new, since October 7, 2023, it has become more and more suffocating.

In June 2024, Israel announced that it would legalize five unauthorized settlements in the West Bank, according to CNN. The International Court of Justice has declared Israeli settlements in the West Bank violate international law, including provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits the transfer of an occupying power’s civilian population into occupied territory. Yet Israel has been expanding the number of settlements and funding them at an increasing rate since October 7. According to the Times of Israel, 2023 was the most violent year for West Bank settler violence against Palestinians as tensions continue to escalate during the war in Gaza.

All these escalations have an immense toll on the everyday lives of Palestinians in the West Bank like Mohammed, and have created an overwhelming fear that a full-scale war as seen in the Gaza Strip could spread to the West Bank overnight.