Beneath the Brooklyn Bridge, crowds thoughtfully browsed an outdoor photo gallery featuring the Pulitzer Center’s exhibit “Hollowed Out” at the annual Photoville Festival. Despite the rain, photography lovers came out to explore the collection of exhibits, participate in workshops, and hear from the artists themselves. Throughout Photoville's opening weekend, photojournalists and audience members discussed building trust and high school students honed their photography skills in the neighborhood.

For 11 years, the Pulitzer Center has exhibited grantee photography at Photoville, an annual, free photography festival across all five boroughs of New York City. The festival includes in-person and virtual storytelling events, artist talks, educational programming, and open-air exhibitions in parks and other New York public spaces.

Photoville has played a strong role in amplifying and engaging New York audiences with the visual journalism we support. This year’s exhibit featured PublicSource photojournalist Quinn Glabicki’s project, EQT’s Gas Play, which investigated the environmental and human fallout of the company's fracking operations in Appalachia.

Glabicki used photography to creatively document how unseen pollution harms families, jeopardizing their health and homes. For New York communities with their own legacies of industrialism and environmental injustice, these Appalachian stories may have felt remarkably familiar.

“These issues exist everywhere at some scale. It’s almost expected: illness in proximity to industry,” Glabicki said. “How do we document this banality of horror?”

“Hollowed Out”

With the Brooklyn Bridge behind it, the “Hollowed Out” exhibit tells the story of rural communities in northern Appalachia, where the harsh realities of gas extraction hit home. While Pittsburgh gas giant EQT Corporation touts its gas exports as “the largest green initiative on the planet,” abandoned homes and poisoned wells are left in its wake.

Reported and photographed by Glabicki and published by PublicSource, the multimedia project documented families who abandoned their homes in West Virginia after experiencing years of ongoing symptoms consistent with exposure to the chemical compounds released by EQT's operations nearby, as well as residents in Pennsylvania who reported painful rashes and years of undrinkable groundwater after a “frack-out” sent fluid and gas erupting down Main Street.

Glabicki spotlighted the human cost of fracking by weaving portraits of families with stills of packed-up dolls, pages of resident notebooks chronicling health symptoms, air quality complaint investigation forms, and thermal imaging revealing invisible hydrocarbon emissions. Connecting local stories with environmental testing and records created an indisputable public record—one that residents cited when they filed a class-action lawsuit demanding clean water from EQT.

EQT's Gas Play won Pictures of the Year's first place award in the Local News Picture Story category.

“Visualizing the Invisible: Building Trust in Underreported Communities”

During Photoville’s opening weekend celebration, Pulitzer Center and PublicSource hosted a discussion between Glabicki and Stephanie Strasburg on how photographers build trust with communities to tell personal stories that humanize systemic issues. The PublicSource photojournalists explored how documentary photography can uniquely capture undertold stories of resilience and injustice—and inspire community-powered action and change.

Glabicki began by introducing photography from his project, explaining how he first reported on New Freeport, then heard about the families in West Virginia, ultimately realizing the thread that tied it all together was the same company.

He shared how it took time to find the right sources, then more to build trust, before he even took out his camera. “It’s a big risk to go public with these kinds of things,” Glabicki said.

Initially, community members weren’t interested in working with Glabicki. However, they were facing dead ends with EQT and West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP) complaints and beginning to run out of options. By explaining his goals and letting people get to know him as a member of the community, in addition to as a reporter, they eventually allowed him to document their stories.

“In this era of distrust, there’s also a distrust of self,” Glabicki explained. For many of the people he interviewed, it took them many years to attribute and understand their symptoms.

Glabicki worked to document not only the invisible, like air pollutants through partnerships with researchers, but also the inaccessible, such as personal thoughts from journals and interviews. He attributes that success to his continued and patient presence in the community.

“The biggest thing for me is showing up again & showing up again & showing up again,” Glabicki said, and “you’ll be allowed into parts of life that are increasingly intimate or sensitive.”

Glabicki and Strasburg emphasized how the photography humanized what could have been a very technical story, centered on parts-per-billion compounds and federal regulations. While these are key aspects of the story, they can lack a human connection. Photography helped audiences empathize and better understand the real consequences on local individuals.

“In many ways it’s a very local story, but it’s also a very global story,” Glabicki said.

Audience members guided the discussion with their questions on reporting in communities they aren’t members of, knowing when to take the picture, and navigating political differences.

“Visualizing the Invisible: Student Photojournalism Workshop”

On Sunday, Glabicki and Strasburg spent the day coaching high school students during our photojournalism workshop with Press Pass NYC at the Bronx Documentary Center (BDC).

The workshop began with students discussing what news they follow and what they’d like to see more of—they expressed interest in stories on everyday heroes, mental health, and education with solutions angles. After considering how images can contribute to news stories, Strasburg gave a brief overview of composition principles through examples of her work. Students considered how playing with lighting, framing, and focus can determine the story an image tells.

To see these principles at play, Glabicki walked students through images from “Hollowed Out.” They discussed how he visually captured unseen realities to enhance his reporting, carefully crafting a moving story arc about local families.

“You can only photograph pipes and smokestacks so many times, and that only contributes so much to understanding—I actually think it’s quite limited,” Glabicki said.

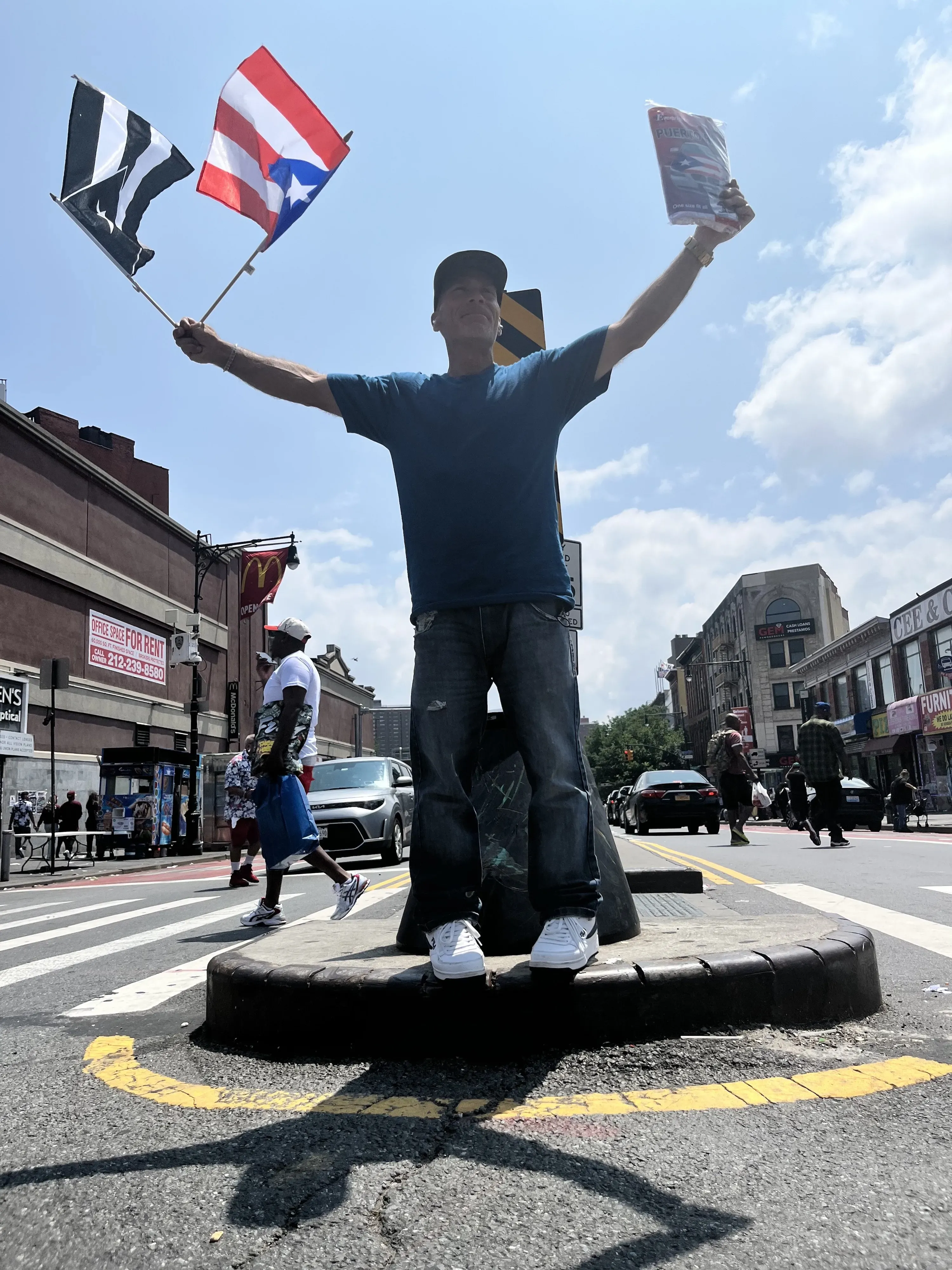

Equipped with these lessons, students got out into the neighborhood to practice. Glabicki, Strasburg, and Ricardo Partida, Youth Education manager at BDC, helped them train their visual eye, coaching students on technical principles as they took their own pictures.

To challenge their storytelling skills, each student had a prompt to inspire a new way of viewing their surroundings. They worked to photograph a feeling, depict consumption, visualize the invisible, or take portraits of local community members.

The workshop ended with students sharing their images, with the group praising their technical strengths and the stories they told. See some of the student images from the workshop below. Thank you to Glabicki, Strasburg, Partida, Lara Bergen, Executive Director of Press Pass NYC, Auhjanae McGee, Press Pass NYC volunteer, and Paul Stremple, Public Programs Manager at BDC, for their help in organizing and running the day.

Student Workshop Photos

Depicting consumption: How do you experience the overconsumption economy in New York?

Resilient nature: How can you use composition to reveal the thin line between destruction and life in the resiliency of nature?

Photographing the invisible: What does it look like to capture a sense or feeling?

Photograph a feeling.

.jpg.webp?itok=MlYXh2QV)