- Endangered angelsharks have been served to schoolchildren in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul for years, as well as in hospitals, clinics, shelters and other public institutions, Mongabay has found.

- We identified 52 tenders totaling more than 211 metric tons of “peixe anjo,” a common name for angelshark, issued by the state and city administrations since 2015.

- As endangered species, angelsharks can’t be caught in Brazil, but imported specimens can be traded legally. Brazil’s IBAMA enforcement agency has requested the environment ministry close this exemption, which some call a loophole.

- After we asked them for comment on past procurements, the state government and two municipal administrations said they wouldn’t buy angelshark anymore.

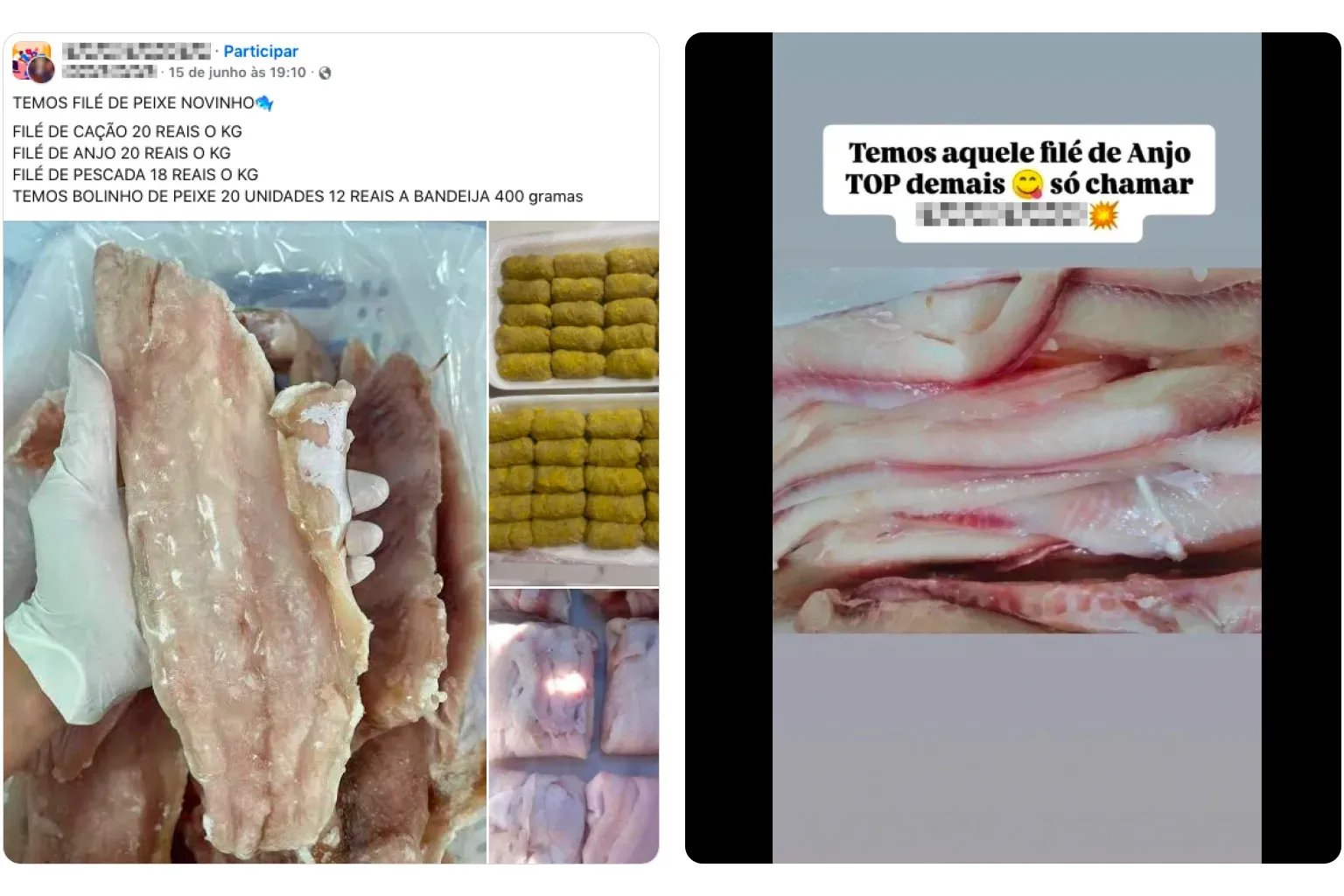

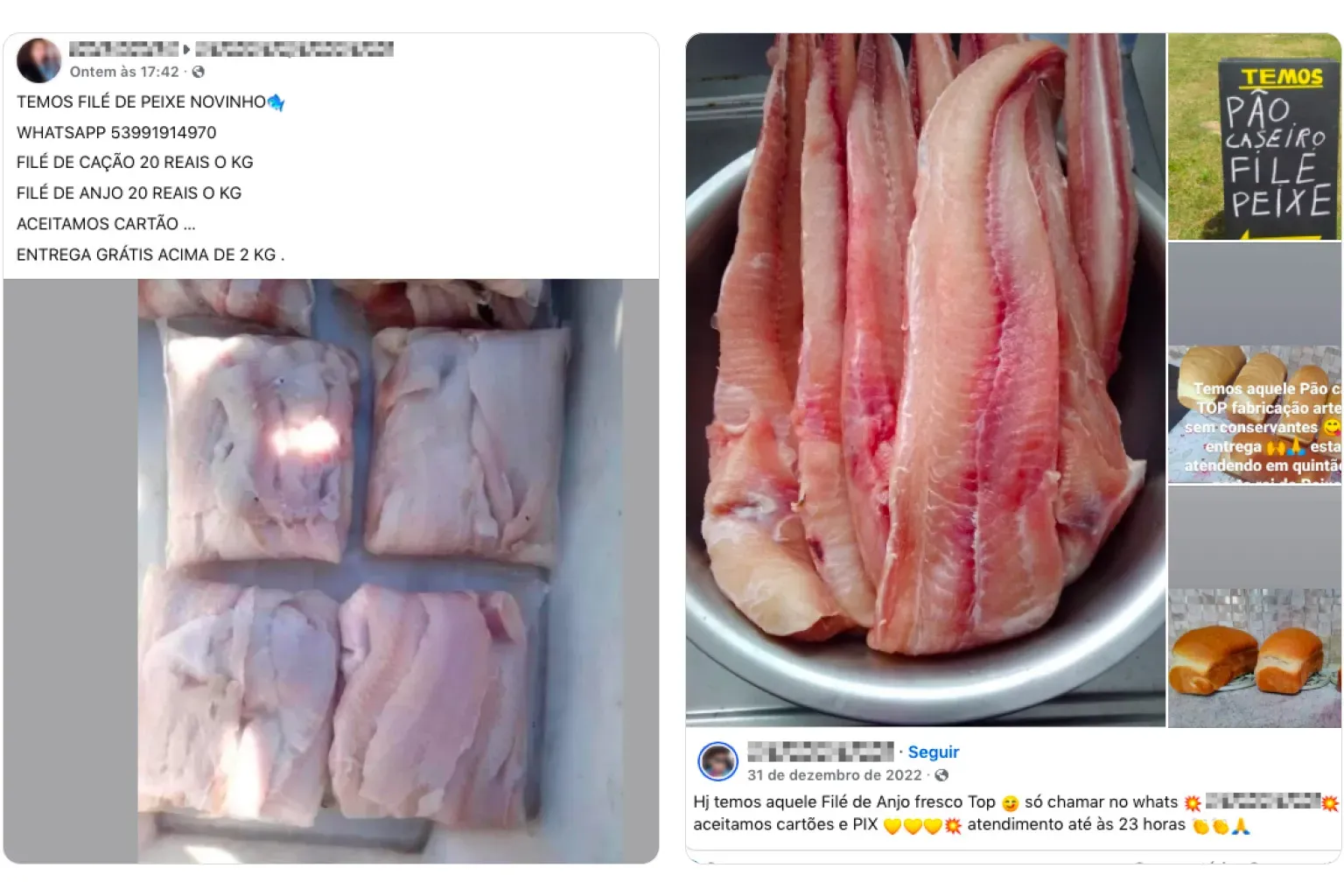

PORTO ALEGRE, Brazil — Delicious, firm and boneless: It’s no wonder peixe anjo, which means “angel fish” in Portuguese, is a top choice at hundreds of schools and early childhood education centers in Brazil’s southernmost state, Rio Grande do Sul. The same goes for dozens of shelters, hospitals, clinics, community centers and other public institutions here.

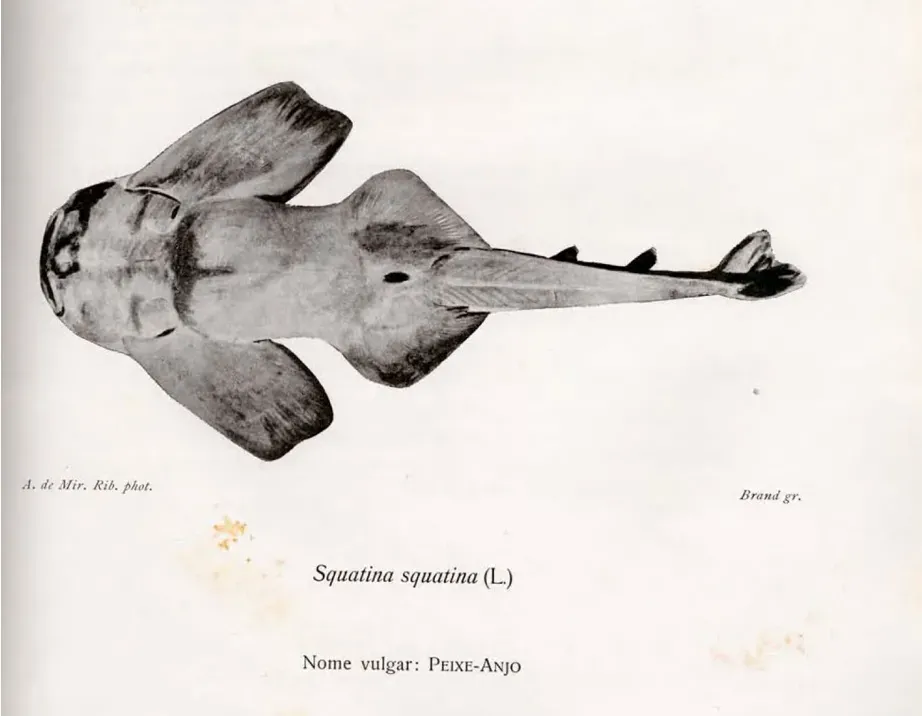

Behind the angelic name, however, are three of the world’s most threatened sharks, all of them illegal to catch in Brazil due to their endangered status: the angular angelshark (Squatina guggenheim), hidden angelshark (S. occulta) and Argentine angelshark (S. argentina).

“I was shocked by this,” Cristina Weissheimer Luft, a municipal nutritionist in the town of Alto Feliz, told us after learning peixe anjo was a reference to angelshark, which she didn’t know until we sent her an interview request. “In our next round of purchasing, there definitely won’t be any peixe anjo.”

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Alto Feliz is one of at least 10 towns and cities in Rio Grande do Sul whose governments have sought to buy large amounts of peixe anjo, Mongabay has found, based on a review of procurement records. Rio Grande do Sul state agencies have also issued at least 11 tenders for peixe anjo, documents show.

Despite their endangered status, trading in angelsharks doesn’t necessarily equate to breaking Brazilian law. That’s because the same environment ministry ordinance that prohibits capture and trade of endangered species makes an exception for imported specimens. In other words, if an angelshark in Brazilian school meals was caught in Uruguay or Argentina, which share a stretch of Atlantic Ocean coastline with Brazil, its trade could be legal.

Tracing the origin of the seafood in these tenders was beyond the scope of our investigation. Doing so can be extremely challenging even for law enforcers and public officials, according to Igor de Brito Silva, coordinator of biodiversity monitoring for Brazil’s environment ministry, who has been trying to rein in the illegal angelshark trade for years.

But while angelsharks are frequently sold in restaurants and fish markets in Rio Grande do Sul, Silva said he was surprised to learn that government procurement teams were buying them by the metric ton.

“It’s alarming,” he said in an interview. “We really had no idea that consumption of a threatened species had become so normalized.”

We discovered the angelshark tenders as part of a larger investigation into public purchases of shark meat in Brazil, the world’s top importer of shark meat. We spent months searching through dozens of government transparency portals and identified more than 1,000 shark meat tenders totaling some 5,400 metric tons in 10 states, recording them in a database published last week.

Most tenders asked for cação, the generic name under which shark meat is sold in Brazil. But 52 requested peixe anjo — angelshark. Fifty of those came from municipal and state agencies in Rio Grande do Sul state, with the remainder from a city in neighboring Santa Catarina state.

The 52 tenders, issued between 2015 and 2025, total more than 211 metric tons of peixe anjo — equivalent to 10 full shipping containers — with a value of 5.7 million reais ($1 million).

We reviewed transparency portals for only a small fraction of Rio Grande do Sul’s 497 municipalities, so there may be additional angelshark tenders we didn’t catch. At the same time, tender quantities represent maximum supply volumes, so actual deliveries may be lower or zero. These numbers do not rule out the possibility that other Brazilian municipalities and states are purchasing angelshark labeled as “cação” when imported.

Just like the nutritionist from Alto Feliz, officials procuring peixe anjo in other municipalities said they didn’t know the term meant angelshark. “No one ever identified that the term used in procurement notices could be referring to a species threatened with extinction,” Clarice de Fátima da Rosa, a nutritionist responsible for school meals in Fazenda Vilanova, wrote in an email (read her full response here).

The official trade name for angelsharks in Brazil is cação-anjo, as established in an agriculture ministry decree. But the federal government’s CATMAT system, used to ensure consistency in how goods are described across procurements, has an item code for a fish described simply as anjo. In practice, the term anjo or peixe anjo is often used in restaurants and fish markets in southeast Brazil as a label for angelshark, according to Patricia Charvet, biology professor and visiting researcher at Brazil’s Federal University of Ceará and regional vice chair of the Shark Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission.

“Calling it angelfish is a lot prettier than calling it cação, not to mention tubarão,” said the environment ministry’s Silva, using the Portuguese word for shark.

Besides the obvious conservation issues with buying endangered sharks by the containerload, the angelshark procurements also raise public health concerns. As apex predators, sharks bioaccumulate heavy metals like mercury and arsenic. While excessive exposure to these substances can harm anyone, children “are at greater risk because they have less body weight and are still developing,” said Rachel Hauser-Davis, a British environmental researcher based at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, known as Fiocruz, a research institute affiliated with Brazil’s Ministry of Health.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration advises children and pregnant women to refrain from eating shark meat due to mercury and other contaminants. Brazil’s Ministry of Health, however, recommends shark meat for children under 2, due in part to sharks’ lack of bones, which are seen as a choking hazard. The Gravataí municipal government, for example, said in a statement that it purchased peixe anjo because its boneless flesh made it “more suitable for the diet of children and the elderly, offering zero risk of choking.” (The health ministry did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

While numerous studies show shark meat often contains high levels of heavy metals, none appear to have tested angelsharks specifically. However, Hauser-Davis told us preliminary data collected by her team from angelsharks taken in Rio de Janeiro indicate “their consumption most probably presents a risk.” Although angelsharks are not apex predators in the same way many other sharks are — they lie in wait for their prey in the sand on the ocean floor — their lifestyle increases their chances of contamination, according to Hauser-Davis. That sediment, she said, is “what we call a sink of chemical contaminants, because most contaminants eventually settle from the water column into the sediment.”

Industry groups representing companies involved in shark fishing and trade tend to dismiss concerns around heavy metals, including mercury and arsenic. “The cação sold in Brazil does not contain any type of contamination and therefore does not pose a health risk to consumers,” the Brazilian Association of Fish Industries, known as Abipesca, said in a statement published last week.

Like Alto Feliz, the Palmares do Sul municipal government (full response here) and the Rio Grande do Sul state administration (full response here) said after hearing from us that they would no longer include peixe anjo in meal programs. “In alignment with biodiversity protection strategies, the state government will instruct all its agencies to remove the species from procurement tenders, replacing it with a non-threatened fish species,” the Rio Grande do Sul administration told us.

Porto Alegre, the state capital, requested more peixe anjo than any other municipality in our data, with 83.2 metric tons, followed by Gravataí at 59.5 metric tons. Sara Bortoluz, coordinator of Porto Alegre’s school feeding division, told us peixe anjo was no longer part of its purchasing program (full response here). Gravataí, meanwhile, whose social assistance department requested peixe anjo in a 2025 procurement, said it would “continue to monitor the situation in case adjustments to procurement requests become necessary” (full response here).

The full responses from every Rio Grande do Sul administration that we found issuing a peixe anjo tender are listed at the end of this article.

In an email to Mongabay, the National Fund for Education Development, known as the FNDE, which oversees Brazil’s National School Feeding Program, said it was “not within its remit to authorize or prohibit the use of specific animal or plant species” and that it was the responsibility of states and municipalities to ensure compliance with environmental rules. (Full response here.)

The Regional Council of Nutritionists — 2nd Region (CRN-2), a government body that oversees the practice of nutrition in Rio Grande do Sul, said “there is no explicit legal prohibition regarding the importation of the species — which does not mean, however, that its consumption is encouraged by nutritional guidelines.” (Full statement here.)

Angels in the black market

The angelsharks of Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina inhabit the floor of the Southwest Atlantic up to about 350 meters (about 1,150 feet) in depth. With flat, broad-chested bodies, they look more like rays than the typical shark and are masters of ambush: They hide under the sand with only their eyes poking out, before applying a lethal strike to a fish, crustacean or mollusk.

But angelsharks are often caught as bycatch by certain types of fishing nets fastened to the seafloor, or by bottom trawlers dragging their nets across the seabed. “There is no place where angelsharks are safe from fishing,” Roberta Aguiar dos Santos, who coordinates Brazil’s National Action Plan for the Protection of Endangered Marine Sharks and Rays (PAN Tubarões) at the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, known as ICMBio, a federal agency that manages protected areas, told Mongabay.

The result is these angelsharks are fast disappearing. The IUCN classifies S. guggenheim as endangered and S. occulta and S. argentina as critically endangered. Both Brazil’s environment ministry and the Rio Grande do Sul administration list all three as critically endangered.

“Angelsharks are one of the most threatened groups of shark species,” Chris Mull, a postdoctoral research fellow at Canada’s Dalhousie University who is studying the global shark meat trade, said by phone. “They have very few strongholds left.”

It remains unclear whether the procurements we identified sourced imported angelsharks or illegally caught ones from Brazilian waters. The latter possibility, Silva said, could not be ruled out. “Today our traceability is not consistent enough to guarantee the legal origin [of the product],” he said.

S. guggenheim and S. occulta are among the most frequent bycatch in Brazilian commercial fisheries, meaning vessels targeting other species often end up pulling in angelshark. While Brazil allows the sale of some types of bycatch, endangered species must be returned to the sea, even if they’re dead. But that doesn’t always happen — especially when there’s a market for the fish.

Luiz Eduardo Bonilha, an environmental analyst and inspection officer in Porto Alegre for IBAMA, a regulatory and enforcement arm of Brazil’s environment ministry, explained how it works. Angelsharks, he said, “are placed in a corner of the [ship’s] hold, and when the boat enters the port, this cargo is transferred to a smaller vessel which is strategically located for quick removal.” There are records of this practice, he said, in the municipality of Rio Grande in the south of Rio Grande do Sul state and in Passo de Torres on the southern coast of Santa Catarina state. “It’s very difficult for us to catch these transfers because they are done in remote areas where inspections are not operating 24 hours a day, during the wee hours of the morning,” he said.

This is likely how approximately 1 metric ton of angelshark ended up in a house in Guaíba, another city in Rio Grande do Sul, where they were stored in precarious sanitation conditions, authorities said. “They were literally processing the fish on tables inside a garage,” said Col. Rodrigo Gonçalves dos Santos, chief of environmental command of the Military Brigade of Rio Grande do Sul, who participated in a raid on the premises earlier this year as part of a joint operation with IBAMA and the Bureau of the Environment and Infrastructure of Rio Grande do Sul, a state agency.

“There were no invoices — it was an illegally transported product,” Bonilha said. At the locale, agents also found other endangered species such as catfish, guitarfish and two types of hammerhead sharks. Eight people were detained and face sentences of 1-3 years in prison and fines up to 10,000 reais ($1,800) for every shark captured.

The origin of the animals is still under investigation, but according to inspection agents, such cases are common throughout Rio Grande do Sul. “This is a very large network,” Col. Gonçalves dos Santos said. “It’s not just one supplier — there are several.”

Gonçalves dos Santos’ assertion is supported by the ease of purchasing angelshark meat in the state. In a quick Facebook search, Mongabay found fish described as peixe anjo or cação-anjo for sale in coastal cities like Cidreira, Pinhal, Tramandaí and Rio Grande as well as in São Lourenço do Sul on the banks of the Lagoa dos Patos lagoon and Alvorada in the Porto Alegre metropolitan region. Authorities have also seized angelshark on sale in São Paulo and Santa Catarina states.

In a search of IBAMA’s database, Mongabay found 47 fines related to the fishing, transportation or storage of angelshark, with 36 of those in Rio Grande do Sul. The fines were issued between 2005 and 2022 and totaled 35.3 million reais ($6.4 million). The actual numbers could be much higher, however, as the type of fish seized was not always identified in the infraction reports.

Through artisanal beach seining alone, Bonilha estimates that between 1,000 and 2,000 tons of angelshark and Brazilian guitarfish (Pseudobatos horkelii, a species of bottom-dwelling ray) are caught every year along the Rio Grande do Sul coast — and these, he said, are the endangered fish most targeted. “When they’re caught using trawl or gillnet methods, we’re talking about several thousand boats, so the numbers could go well beyond that,” he said.

Some of the illegal angelshark processed in the Guaíba garage was sold at a stall in the Porto Alegre Public Market, where angelshark meat was previously seized in 2022. This time, agents identified the Guaíba fraud thanks to an invoice discrepancy: The document presented by the vendor was for imported frozen fillets, while the fish on sale at the counter was fresh and cut into pieces. “It was laundering,” Bonilha said, referring to the practice of using forged import papers to smuggle illegal cargo into legal supply chains.

The possibilities for fraud are endless, from document tampering to the misuse of a genuine import invoice. “Because the product is frozen, [the retailer] uses the same invoice for a long time to justify any product they have on the shelf,” Bonilha said. “A frozen product has a two-year shelf life, so they present the same invoice for any inspection and say, ‘I bought this last year, it was frozen.'”

The creation of a domestic consumer market for endangered species and the “laundering of illegal fish via false declarations of volume on unreliable invoices” were two of the reasons cited by Jair Schmitt, IBAMA’s director of environmental protection, in an April letter calling for Brazil to ban imports of endangered species. The document also says “it is probable that animals protected in Brazilian jurisdictional waters are the same ones caught in neighboring countries and subsequently imported to Brazil.”

Brazil’s environment ministry told us the letter was being processed by the Department of Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity (DCBio). According to the ministry, “The process in which the official letter is included is under review and there is no forecast for its conclusion.”

According to Silva, the information gathered by Mongabay makes a review of the legislation even more urgent. “The possibility that these companies may be marketing large quantities of a protected species mobilizes us even more to try to understand the process and perhaps work to discourage this type of importation.”

Angels beyond borders

One of the difficulties in determining the origins of the fish consumed in Rio Grande do Sul is that traders are not required to identify the species of the animal when exporting or importing the product. The limited data available on Brazilian Squatina imports come from the Argentine and Uruguayan governments, where the capture of these species is permitted within certain regulations that vary depending on the fishing location.

In the shared fishing area between Argentina and Uruguay, where studies indicate most shark and ray catches occur, there is a quota for angelshark fishing. According to the binational commission that manages the region, commercial landings of angelsharks in this region dropped by 85% from 2008-2016, evidence of a population decline.

In Argentina, where angelsharks are known as pez ángel (angelfish) or pollo de mar (chicken of the sea), some 1,500 tons are caught annually, according to the Undersecretariat of Fishing and Aquaculture. Brazil is virtually the sole buyer of Argentina’s angelsharks, accounting for at least 99% of its neighbor’s exports. Shipments, however, have trended downward since 2016: The latest data, from 2024, indicate only 100 tons of imports from Argentina.

Data from the Uruguayan government are scarcer and more outdated. In 2018, Uruguay’s fisheries ministry recorded the capture of 153.62 tons of angelito, as angelshark is known there. That same year, Uruguay exported 41.2 tons of the fish, but there is no information on where it was shipped.

Mull, the Dalhousie University researcher, said some of Argentina’s angelshark might pass through Uruguay, a major shark processing hub, before heading on to Brazil. He raised the possibility that some illegally caught Brazilian angelshark might follow a similar path. “Fishermen may not have large processing plants capable of handling such large species or in such large volumes, so it’s easier for them to simply sell the product to processors in Uruguay, who process it and ship it back [to Brazil],” he said.

Given the angelshark volumes in public tenders, plus likely additional tenders we missed and the animal’s prevalence in southeastern Brazil’s restaurants and markets, Silva said he doubted imports alone could meet demand. “I think it’s quite likely that not all of it is imported,” he said. “But an investigation is definitely necessary.”

Angel investors

The 52 angelshark tenders in our data were awarded to nearly 30 supplier companies, documents show, with some winning multiple tenders. Some offer their own brands, while others distribute fish from other companies. Suppliers with the largest delivery volumes in our data are Maxigiro Comércio de Alimentos, Pommar Comércio De Alimentos, Distrasul Comercio e Representação and Burlani Comércio de Carnes, all from Porto Alegre, and Comprandomais Comercio De Pescados, based in Santa Catarina state.

A Maxigiro employee told us in a message that the company no longer worked with fish (full response here). One of Pommar’s owners said the same thing by phone. The other top companies didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The brands most frequently cited by the winners of angelshark tenders as candidates for provision are Frumar Frutos do Mar, Burlani Comércio de Carnes and Costiero from Rio Grande do Sul; Costa Sul Pescados and Atlantico from Santa Catarina; and Great Food (Vivenda do Camarão) from São Paulo state.

Frumar, which calls itself “Brazil’s largest salmon and seafood industry” had its brand named by the winners of nearly half the bidding processes in our data (a single tender often names multiple brands). In 2019, IBAMA fined the company 6,000 reais ($1,090) for having 12 kilograms (26 pounds) of angelshark fillets in storage without proper documentation. Frumar did not respond to Mongabay’s inquiries.

We sent the other five top companies inquiries about the origin of their angelshark with the exception of Atlantico because our team was unable to make contact with it. Costa Sul and Great Food (Vivenda do Camarão) said they didn’t work with angelfish (full responses here and here). Burlani and Costiero didn’t respond.

One of the difficulties in tracing the origin of fish in Brazil is the lack of standardized product labeling. A 2024 study published in the journal Biological Conservation identified incorrect labeling on 237 seafood products sold in the country. The researchers also stated that 64 of the 203 Brazilian ray species are being sold on the market, usually under the generic term cação.

Two other studies, from 2018 and 2021, based on genetic analyses of fish sold in different Brazilian states, found both S. occulta and S. guggenheim being sold under this same label. “Sharks of various species are being sold as cação,” ICMBio’s Aguiar dos Santos said. “Labeling should be a priority issue for us to solve.”

Added to this is the challenge of identifying the species after the fish has its fins and head removed and is cut into steaks or fillets. “The criminals systematically make the animals unrecognizable,” IBAMA’s Bonilha said. Often, environmental agents’ only alternative is to perform a genetic test, which takes about 30 days. Silva said IBAMA would soon have equipment that performs this analysis within two hours.

But what the inspection team most needs are tools that increase transparency in the Brazilian fish market. “We have been asking for a system that provides this traceability to the regulatory agency and to the public,” Silva said. “Because currently, no one has it.”

Until then, Silva said, consumers and government agencies in the market for peixe anjo probably couldn’t be sure they weren’t buying illegally caught angelshark. “When in doubt, don’t buy a threatened species,” he said. With these fish, “The probability that it’s illegal is already high.”

Responses from municipal and state government agencies:

The municipal governments of Taquari, Esteio, Santa Cruz do Sul, and Gramado did not respond to Mongabay’s inquiries.

Alto Feliz

Nutritionist Cristina Weissheimer Luft, responsible for developing public school lunch menus in Alto Feliz, wrote in an email that 943 kg of peixe anjo had been consumed over the last three years and that she had no knowledge it was an endangered species. She added by phone that no new acquisitions of the fish would be made.

Alvorada

The municipal government said the current administration was not involved in issuing the lone tender we identified from this city, which occurred in 2015, and could not clarify the reasons behind it. The current administration, it said, had not purchased endangered species. Read the full response here.

Fazenda Vilanova

Clarice de Fátima da Rosa, the nutritionist responsible for school meals in Fazenda Vilanova, said peixe anjo was requested in food procurements “because it is a generic term frequently used in regional trade to identify certain types of fish with white flesh and no visible bones, intended for children,” and that her team was unaware it referred to an endangered species. Although we identified two peixe anjo tenders issued by the municipal government, in 2024 and 2025, Rosa said no deliveries of peixe anjo had been made to date. Read the full response here.

Rio Grande do Sul state

The state administration of Rio Grande do Sul emphasized that peixe anjo could legally be imported and that there were currently no open tenders in the city for the purchase of the fish. Even so, it said it would “instruct all its units to remove the species from the procurement tenders, replacing it with another non-threatened fish species.” Read the full response here.

Gravataí

The Gravataí city government said it had chosen peixe anjo due to its boneless flesh, making it more suitable for consumption by children and the elderly. It added that “there is no general prohibition on the capture of peixe anjo, but rather regulations, and [the administration] will continue monitoring in case adjustments are needed in purchase requests.” Read the full response here.

Palmares do Sul

The Palmares do Sul municipal government said it had so far made one purchase of peixe anjo, as it was “a type of fish already approved by the students” and readily available. It emphasized that Brazil’s National School Feeding Program did not prohibit its purchase, but added that it would no longer purchase it going forward. Read the full response here.

Porto Alegre

The coordinator of Porto Alegre’s School Meals Office wrote in an email that peixe anjo had not been part of the city’s procurement program since the end of 2021. The city’s press office said the municipal executive branch did not purchase peixe anjo, and that the item “is even deactivated in the City’s system.” Read the full response here.

Citations:

Hauser-Davis, R. A., Wosnick, N., Chaves, A. P., Giareta, E. P., Leite, R. D., & Torres-Florez, J. P. (2024). The global issue of metal contamination in sharks, rays and skates and associated human health risks. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 288, 117358. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.117358

De Carvalho, G. G., Degaspari, I. A., Branco, V., Canário, J., De Amorim, A. F., Kennedy, V. H., & Ferreira, J. R. (2014). Assessment of total and organic mercury levels in blue sharks (Prionace glauca) from the south and southeastern Brazilian coast. Biological Trace Element Research, 159(1-3), 128–134. doi:10.1007/s12011-014-9995-6

Alvarenga, M., Bunholi, I. V., De Brito, G. R., Siqueira, M. V., Domingues, R. R., Chauvet, P., … Da Cruz, V. P. (2024). Fifteen years of elasmobranchs trade unveiled by DNA tools: Lessons for enhanced monitoring and conservation actions. Biological Conservation, 292, 110543. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110543

Almerón-Souza, F., Sperb, C., Castilho, C. L., Figueiredo, P. I., Gonçalves, L. T., Machado, R., … Fagundes, N. J. (2018). Molecular identification of shark meat from local markets in southern Brazil based on DNA Barcoding: Evidence for Mislabeling and trade of endangered species. Frontiers in Genetics, 9. doi:10.3389/fgene.2018.00138

Merten Cruz, M., Szynwelski, B. É., & Occhotoreena de Freitas, T. R. (2021). Biodiversity on sale: The shark meat market threatens elasmobranchs in Brazil. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 31(12), 3437–3450. doi:10.1002/aqc.3710