The morning of the 2024 National Day of Greenland, celebrated on June 21, was cold. A thick veil of fog hung heavy on the horizon, touching the sea below and making it hard at some distances to distinguish sky from water.

The dreary background only made the town's colors brighter. Red-and-white Greenlandic flags billowed in the wind as locals passed a rainbow of houses on their way to the shore. Even the traditional Inuit dress served as a beacon, with its combination of patterns and contrasting colors.

It was as if someone splattered vibrant paint onto a gray canvas.

To the outside world, Greenland is a stunning microcosm of the climate crisis, featured in headlines warning of a grim, uncertain future—temperatures rocketing, ice melting into a rising sea, an island's landscape shrinking before the locals' eyes.

But here in the capital, as children ran carrying bubble wands and a choir's melody sounded through the town square, that all felt very far away.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

The locals spoke of climate change with a resigned matter-of-factness. The Inuit are used to adapting, they said, having done it for thousands of years in an ever-changing Arctic. They are finding ways to hold on to tradition while embracing the new realities of their environment.

The climate is changing, one resident said plainly. All Greenlanders can do is change with it.

For four decades, Greenlanders have gathered on the summer solstice, also known as the longest day, to celebrate their national identity. Cities across the map host a day's worth of festivities highlighting Inuit culture. In Nuuk, the holiday began with a seal hunting competition.

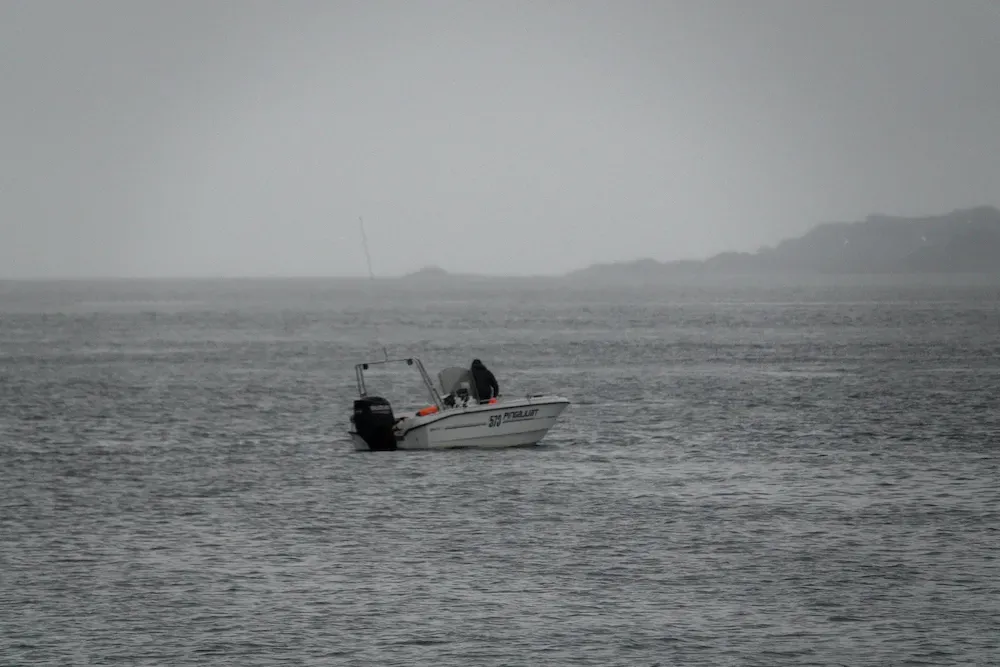

The sound of cannon fire reverberating down the narrow streets signaled the start of the hunt. Dozens of fishing boats sped from the harbor into the open sea, their wakes crossing in the dark teal water.

The first to return with a freshly caught seal wins.

After what seemed like only minutes, a crowd of people rushed down to the water to meet a returning boat. As it neared, the onlookers stood on their toes and craned their necks to try and catch a glimpse of the seal among the boat's bloodied interior.

The hunter smiled. He had just won.

Seal hunting is an important part of Inuit culture, providing food and clothing to much of Greenland's population. But as the sea ice melts, it has become harder in some areas to hunt seals, particularly in the northern part of the island where sturdy sea ice no longer forms during the winter months.

A strong connection to nature is at the core of Inuit life. On days when the weather is nice, people hike among Greenland's hills or kayak and sail in the still waters. They pick berries, too, though locals say they are now harder to find because of the changing climate. Nature is integral to many traditions—hunting, fishing, sailing. But it's also a place of healing.

"The land is where you get strength, the land is where you get food, the land is where you boost your mental health," said Ingelise Olesen, the research coordinator at the Center for Public Health in Greenland and an Inuit grandmother.

"The land is connected to you in a very special way."

Earth's warming has rapidly altered Greenland's environment.

One can see the changes. The Greenland Ice Sheet, which covers 80% of the island, has lost around 270 billion metric tons of ice each year since 2002. The sea ice that once formed a sort of road system for Greenlanders to travel on with sled dogs and snowmobiles has grown thinner and less stable. Storms are stronger, the animals have moved, and locals say the air feels warmer than it did only a few years ago.

What hasn't changed is the resilience of the people.

"We are good to adapt," Olesen said with a smile. "We have done it for thousands of years."