Pulitzer Center Update January 24, 2025

Nature Speaks Up: 'If the Walls Can Talk' Art Exhibition Ends With Community Reflection on the Fragility of Nature

Country:

Nestled in the heart of Manila, Escolta is a heavily urbanized district that has undergone cycles of destruction and renewal since the 1600s. A witness to much of Philippine history, it has evolved from being the gateway to one of the world's oldest Chinatowns to hosting German businesses during Manila's peak as a global city in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and later, rebuilding after the devastation of World War II.

Amid this storied landscape stands the First United Building, a prominent landmark welcoming visitors from the bustling Divisoria shopping district. This historic site served as the venue for the Pulitzer Center's latest exhibition, If the Walls Can Talk, held on December 12-31, 2024.

As the northeast monsoon swept across the city, bringing cool winds from mainland Asia to temper Manila's heat, visitors gathered to view the thought-provoking works on display. One striking piece featured visual metaphors of uprooted lives and ecosystems, offering a poignant reflection on the interconnectedness of human and environmental struggles.

“I haven’t been able to attend many art exhibits, but I like how this one touches on environmental issues, especially the lives of tribes[people]. I’m a nature person, I like nature stuff, I keep updated on environmental issues so seeing the art was very nice. I had to get help from some of my friends to interpret the art, but after understanding the works, my favorite was the one about dying trees, the glass and resin and [cyanotype]. It reminded me of the fragility of our world.”

— Junior high school student

Walls form the foundation of our homes and buildings are silent witnesses to the lives lived within and beyond them. These structures have evolved alongside human civilization; have offered protection, shelter, and a sense of permanence in an ever-changing world. But they also hold stories—of growth and decline, creation and destruction—that reflect the shifting landscapes they inhabit.

According to a 2021 report by Karol Ilagan from the Pulitzer Center, the Philippines was once covered by lush forests, which made up over 90% of the country’s land area before colonial rule. Over time, population growth and land use changes led to a sharp decline in forest cover. By the end of American rule, forests had already shrunk significantly, and the loss accelerated during martial law. Despite ongoing efforts to restore the forests, they still cover less than 7 million hectares of the country today.

The dwindling forests tell a larger story of urbanization and industrialization as cities expand and consume spaces once populated by flora and fauna. This narrative resonates strongly with the First United Building in Manila, a heritage structure in a city where the push for progress often clashes with the remnants of the past. Within and outside its walls, we are reminded of the tensions between preservation and transformation, the natural and the constructed, and the lives that intersect these realms.

In this exhibit, artists Eunice Sanchez, Kookoo Ramos-Cruda, and Resty Flores tell stories confronting nature and humanity, inspired by reports from the Pulitzer Center. Eunice Sanchez reflects on the sustainability of the Masungi Georeserve in Rizal, a 20-year reclamation of deforested land, and its capacity to inspire broader environmental action. Kookoo Ramos-Cruda turns our attention to the waterways of Rio Tuba in Palawan, where nickel mining limits access to clean water, inviting reflection on the unequal realities of water scarcity. Lastly, Resty Flores sheds light on the plight of Indigenous peoples affected by the Mining Act of 1995, as he bares their deep-rooted connection to the land and the dislocation they face when stripped of it.

—LK Rigor

Curator

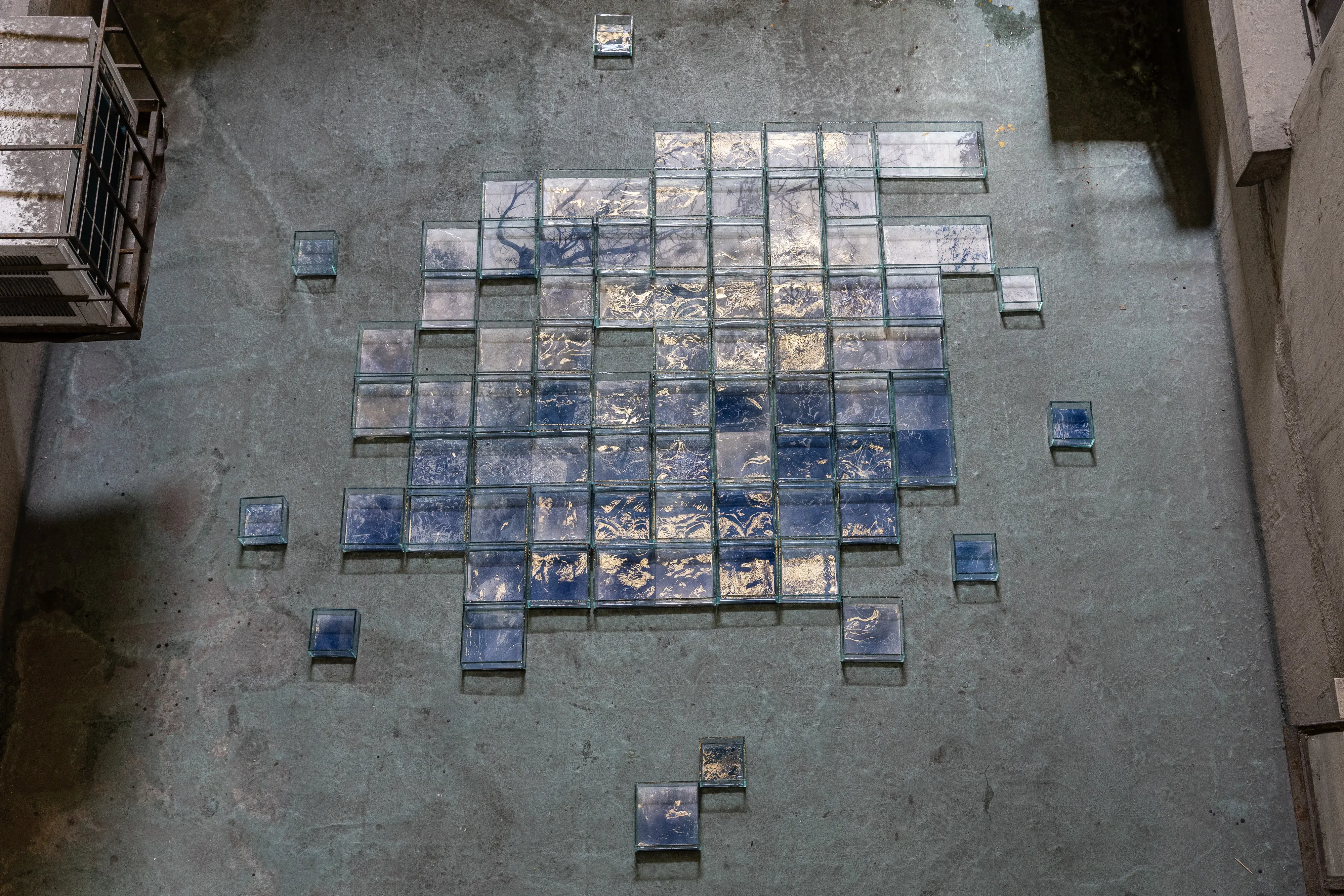

'Di Kalaunan'

Cyanotype on watercolor paper, resin, and glass

Variable dimension

2024

Eunice Sanchez’s “Di Kalaunan” reflects on humanity’s tenuous relationship with nature and the collective reckoning with environmental degradation. The installation features a single image of foliage, fragmented into cyanotype squares and layered with resin, embedded in glass panels. Once assembled, the squares form a complete image, evoking themes of fragility and impermanence. Displayed in an open space, the resin and glass capture and distort elements of the surroundings, with the sky becoming both a canvas and a symbol of nature’s enduring claim.

The cyanotypes are subject to fading under prolonged sunlight—a process intentionally left to unfold during the exhibit. This inevitable transformation mirrors the slow disappearance of nature and the stories tied to it, challenging viewers to question their role in the systems perpetuating environmental loss.

Sanchez’s deeply introspective approach acknowledges her privilege and distance from firsthand experiences of deforestation. By weaving her reflections with the borrowed narratives of those most affected, she emphasizes the gaps between memory, responsibility, and action. The work asks: how can we confront the vulnerabilities created by flawed systems, and when will we begin showing up for the losses we’ve long overlooked?

Through “Di Kalaunan,” Sanchez offers not answers but an urgent invitation to reckon with the consequences of human neglect and to reimagine our collective role in fostering accountability and care for the environment.

'Anino ng Kasagsagan'

Digital print on Duchess satin; Acrylic and oil pastel on canvas;

31 x 67 inches print on Duchess satin

2024

Kookoo Ramos-Cruda draws attention to the environmental and human cost of mining in Palawan through her artworks. Her canvas references images from a Pulitzer Center report, including one of Narlito Silnay, a community leader and member of the Pala'wan tribe. Silnay and his community live along the Tuba River, where nickel mining has left remarkable damage to the forest. In the print, he stands at the confluence of two polluted water sources. In another print, a journalist collects a water sample from the Tuba River.

Taking her work beyond the canvas, Ramos-Cruda transfers her paintings onto fabric, hanging them along the staircase of the First United Building. As viewers move through the space, the act of ascending and descending encourages a deeper reflection on the layered impacts of mining on land, water, and the lives connected to them.

As both a mother and an artist, Ramos-Cruda brings a personal urgency to addressing environmental degradation, driven by her concern for the future of her children and generations to come. Her work calls attention to the importance of listening to those most affected by environmental damage, highlighting the need to challenge systems that prioritize industrial profits over the well-being of nature and people. Through her art, she asks: How can we hold systems accountable and create fair solutions to heal what has been damaged, ensuring a better world for future generations?

“Rooted”

Woodcut on vinyl, woodcut on polyethylene plastic, woodcut on cloth

60 x 108 inches

48 x 95 inches (relief)

2024

“Taruk”

Woodcut on polyethylene plastic, woodcut on silk cloth

43 x 108 inches

30 x 88 inches (relief)

2024

“‘Rooted’ plays on irony, wherein the familial image is flattened and desaturated; the family is displaced and commodified, displayed out in Escolta’s open air, right next to “lot of sale” advertisements.”

—Aidan Bernales and Gabe Fernandez writing for Heights publication

Resty Flores highlights the struggles of Indigenous peoples and local communities against environmental and cultural displacement in his works. Drawing from firsthand experiences with Lumad and Aeta communities, he reflects on shared narratives of land loss, environmental degradation, and the erosion of cultural practices caused by exploitative policies and corporate interests.

The Mining Act of 1995, which facilitates large-scale mining on ancestral lands, serves as a backdrop to Flores’s exploration of the connections between land, culture, and identity. He portrays Indigenous peoples as primary stewards of nature, emphasizing their deep relationship with their ancestral domains and the threats posed by deforestation and resource extraction.

Flores created “Rooted” and “Taruk” using relief woodblocks, transferring the images onto materials like vinyl, plastic, and silk cloth. The works depict Indigenous figures and barren landscapes—visual metaphors for uprooted lives and ecosystems. In reflecting on these issues, Flores invites us to consider how we can confront the exploitation of land and people, and what responsibility we bear in this ongoing struggle.

The opening day was attended by approximately 60 people including junior high school students, creative academics, media, and the public.

Apart from the main exhibition, a Pulitzer Center-supported film by Shirin Bhandari was also screened at the venue, followed by a media discussion on the topic.

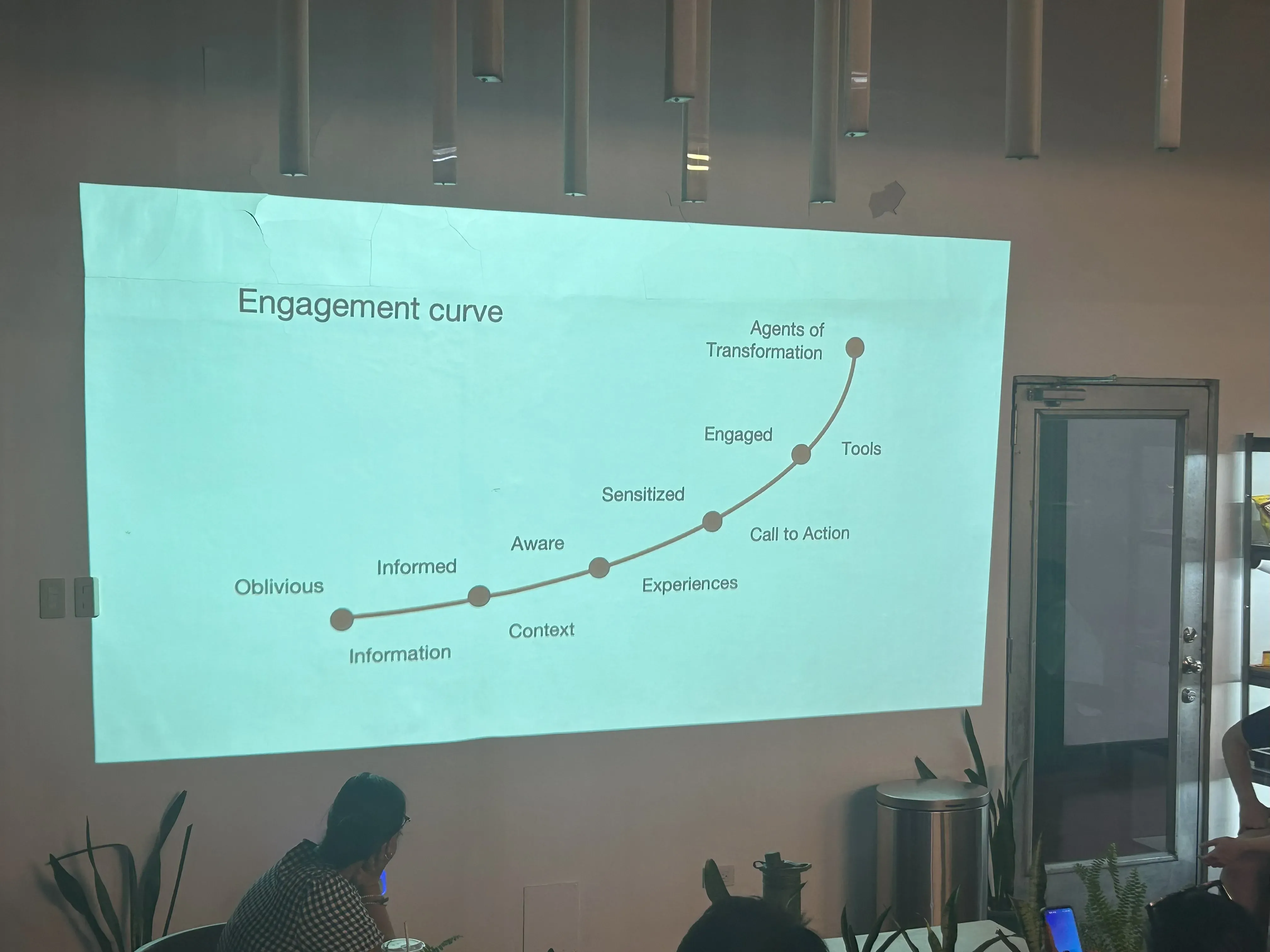

Another public program on the opening day was led by Pulitzer Center grantee Karol Illagan, who presented "Beyond Words and Website: Journalism, Education, and Art."

The exhibition succeeded in raising awareness about environmental and social issues, promoting the integration of journalism and art, fostering community reflection, engaging younger audiences, and demonstrating innovative ways to present art in public spaces.

“I didn’t expect the interaction between journalism and art, which was a pleasant surprise because of learning how dangerous investigative journalism is and how we can help these journalists by using our talents. I was particularly interested in the use of reports as lesson plans [as suggested by Karol Ilagan] as prompts for discussion in class. And the essay, poetry writing contests being held, I think the students will be engaged by that.”

—Carmel Ilustrisimo, creative writing professor, De La Salle University

RELATED INITIATIVES

Initiative

#ShowMeYourTree: The Mekong Influencer Initiative