Floridians who live in manufactured home parks are often older, retired people on fixed incomes who bought property with hopes it would be their “forever home.” Now, lot rents are pricing them out.

Judy Schofield chokes back tears thinking about the memories she made here with her late husband.

From her living room couch, where she sits now, she admires the lighthouses they collected over the years. They’re all shapes and sizes, adorning every room.

It’s something that made this house feel like a home.

“I love this home. I love my yard. And I enjoy living here,” Schofield said. “What's bothering me now is the fact that I'm probably going to have to leave.”

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

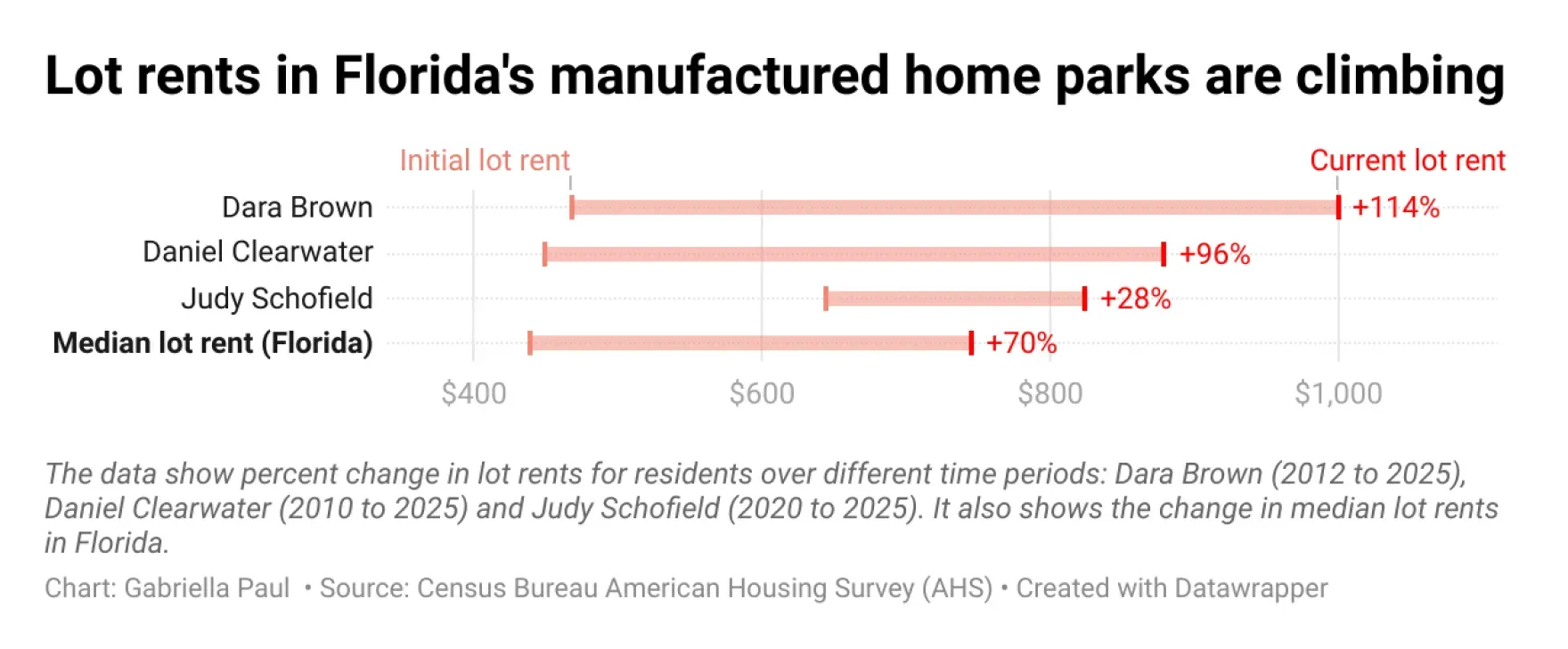

She bought her light blue, single-wide manufactured home in Polk County in 2020 for $25,000. She said the lot rent at Royal Palm Village was still affordable at $645 a month.

Since then, it’s swelled to nearly $800 a month, and counting.

Lot rents are on the rise

Rising lot rents are quietly pricing Floridians out of their communities.

Residents in manufactured home parks typically own their homes, which are cheaper than site-built homes, and rent the lot underneath it.

From 2015 to 2023, median lot rent for manufactured homes has nearly doubled across the state, according to American Housing Survey data from the Census Bureau.

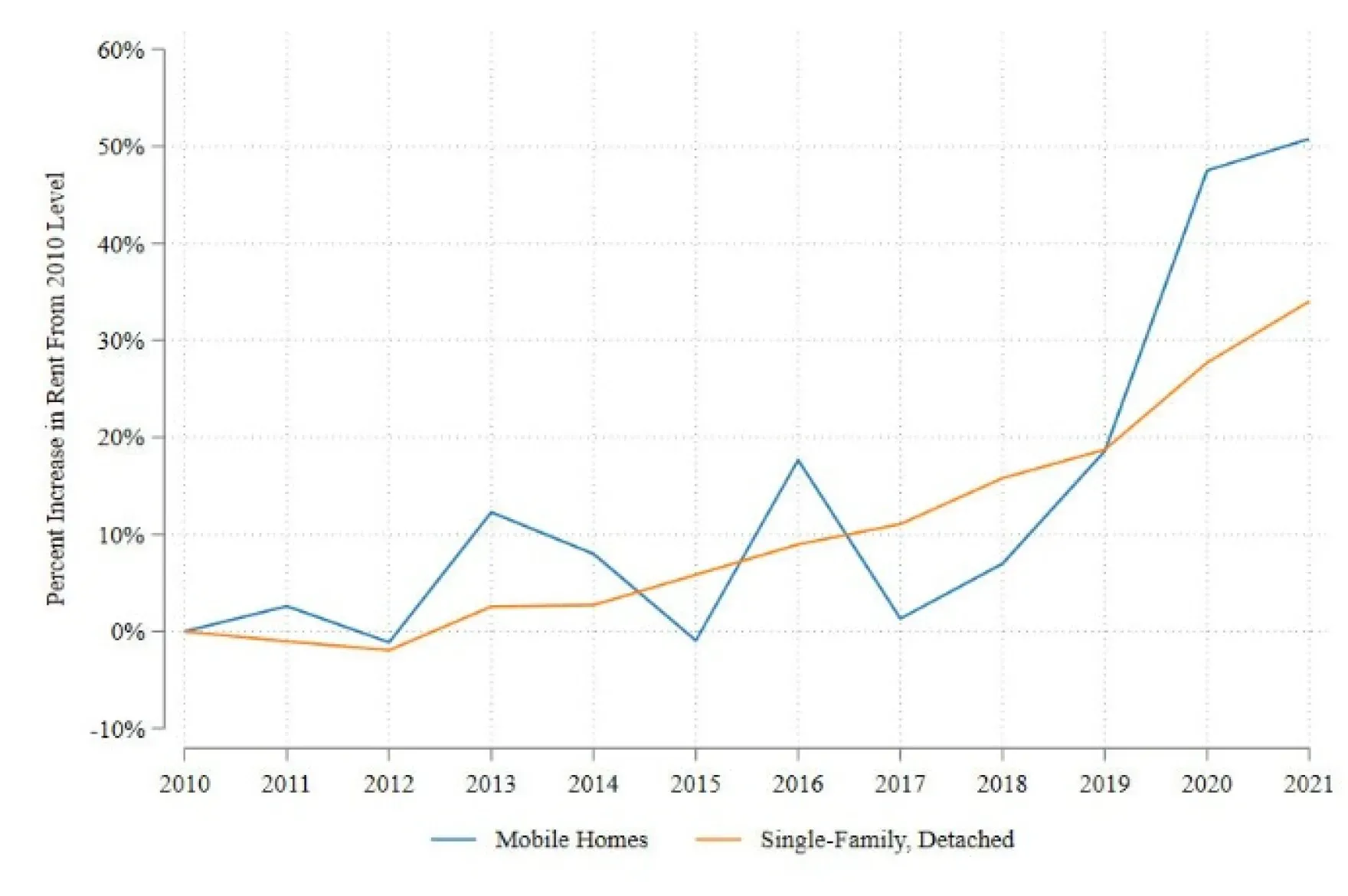

In the Tampa-St.Petersburg-Clearwater metro area, research shows that lot rent in manufactured home parks has outpaced rent for single-family homes over the last decade.

Jeff Grabel, the director of litigation at Bay Area Legal Services, said this signals a shift in the manufactured housing market, which is considered a crucial source of unsubsidized affordable housing for vulnerable individuals.

That’s especially true in Florida, where many residents of manufactured home parks are retirees, veterans and people with disabilities.

“These are folks on fixed income. So $100, $200 extra per month might be doable for someone who’s working, making a decent living, but if you’re on social security, or you have a modest income, that prices you out of the market,” Grabel said.

He said this steady rise in lot rent is forcing people out of the homes they own. And in most cases, there are no good options.

“You're either forced to try to come up with the money, try to sell your mobile home or face eviction,” Grabel said.

Back to work at 86

In Polk County, Schofield is coming up with the money to stay every month.

She said she relies on her daughter to help pay the lot rent, and she had to go back to work. She’s 86.

“It’s a process of going to work making sure that you have enough to pay your bills,” Schofield said. “It’s the stress of not knowing whether you can stay or go. And there’s just so much to it that nobody thinks about. So, it’s a tough time.”

In Pinellas County, Daniel Clearwater is paying double what he did a decade ago.

He’s a veteran who moved from California with his wife, who recently suffered a stroke. He took an early retirement to be her caretaker. They started off in a condo before deciding to buy a manufactured home.

“We moved into a single-wide, and it was under the understanding when we moved in that … we didn't pay for water, we didn't pay for garbage, sewer, any of that,” Clearwater said.

That’s changed.

Additional fees and service charges started showing up on their monthly bill for the first time without much warning.

Grabel said they’re called pass-through fees under Florida Statute Chapter 723, which is also known as the Florida Mobile Home Act. They allow management to charge for services not included in base rent.

“Maybe they have a pool, and there's some servicing regarding the pool, so just those types of services that are not included in base rent,” Grabel said.

Under Florida law, management can pass along these fees, like utility charges and property tax increases, as long as they are considered “reasonable” and are mentioned in a park’s original governing document, which is called a prospectus.

Clearwater said the pass-through fees are something he might be OK with if it meant an increase in park services at Lakeshore Properties.

It hasn’t.

He said the grounds, which are the responsibility of the park owner, are poorly maintained. The streets are prone to flooding, and the culverts are neglected.

“We want out of here,” Clearwater said. “We are just so tired of the lip service here and not getting any actual service.”

Being managed by private equity

Homeowners in situations like Clearwater’s have some options to push back on parks for increases in lot rents, but it often takes legal support and organizing with other neighbors.

“[If there’s] an increase in rent, increase in pass-through fees, but … a decrease in services that they’re supposed to be providing, that’s something you can fight as well and take to court,” Grabel said.

It’s also the subject of a class-action lawsuit that alleges dozens of manufactured home parks across the country conspired “to fix, raise, maintain and/or stabilize lot rental prices for manufactured and modular homes” across markets using reports from Datacomp, a company that markets itself to private equity firms buying up manufactured home parks.

This consolidation is part of a larger trend. A recent report by Next City found that private equity firms now own most of those parks across the country.

And research shows Florida tops the charts as the state with the most parks owned by private equity firms.

“The value of these parks has been going up and up and up, you're talking about millions and millions of dollars to purchase even the most basic-looking, rundown mobile home park,” Grabel said. “They're really worth millions of dollars. Believe it or not, these are cash cows for these private equity firms.”

The move from more “mom and pop” managed parks to large private equity firms, like Brookfield Asset Management and The Blackstone Group, is also connected to worse renter experiences and aggressive eviction tactics.

“If evicted, manufactured-home owners can often only resell their home for a fraction of what they paid for it or cannot resell at all and hand it over to the corporate owner,” according to research from the Private Equity Stakeholder Project.

Grabel said he has seen this strategy used by some park owners across the Tampa metro area, too.

Not so forever home

That was the case for Dara Brown.

She cleaned out her 401K to buy a manufactured home in Riverview. Her lot rent was $468 when she bought it in 2012. In April, it was roughly $1,000 — about as much as her social security check.

She thought about moving it.

Forbes estimates it can cost between $3,500 and $18,000 to move a manufactured home, depending on weight, distance and permitting.

Then she tried to cut her losses.

“I’m between a rock and a hard spot. I’m just going to sell it for as is,” Brown said. “I’m willing to sell my house way, way below market value.”

Brown was evicted before she could do either.

Schofield has also thought through all of her options.

For now, she plans on holding on to her Haines City home. But she often replays the days and weeks leading up to the purchase.

“I thought the way they spoke to us when we were looking at the home was that this was going to be [my] forever home, and that they cared about us,” Schofield said. “And next thing you know, the rent’s going up and up, and you keep thinking: How much longer can I do this?”

She said thinking about moving is hard, but she doesn’t think she’ll have much of a choice.

“As much as I’ve enjoyed it here and everything,” she said, “sometimes I wish now that I had never come.”

.svg_.png.webp?itok=8BDSrLVS)