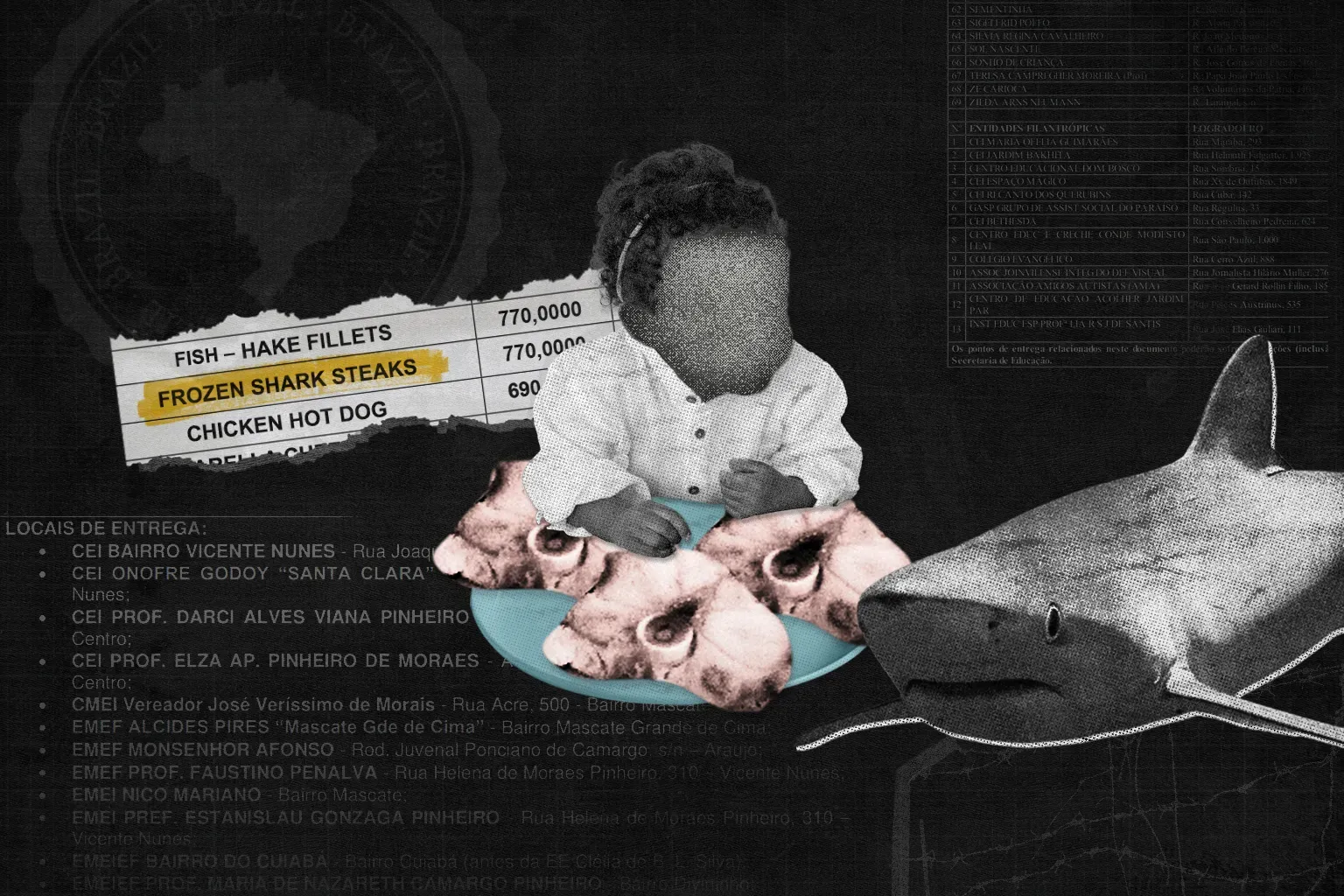

- Brazil, the world’s top importer of shark meat, is feeding much of it to preschoolers, hospital patients, military staff, public workers and more via government procurements, Mongabay has found.

- This influx of shark meat into public buildings is exposing infants and other vulnerable groups to high levels of heavy metals like mercury and arsenic, which accumulate in sharks and can harm human health.

- We identified 5,900 public institutions named as possible shark meat recipients in 1,012 government tenders. The species to be acquired was almost always unspecified, raising concerns that endangered sharks and rays may be entering government meal programs.

Brazilian government agencies are bulk-buying shark meat and serving it in thousands of schools, hospitals, prisons and other institutions, raising serious environmental and public health concerns, a Mongabay investigation has found.

Millions of children have likely been fed shark meat through Brazil’s National School Feeding Program, including infants and toddlers in more than 1,000 day cares and preschools, along with inmates at 92 São Paulo state prisons, the 43,000-strong military police force of Rio de Janeiro state and patients at dozens of hospitals, among others, documents show.

Shark meat is high in heavy metal toxins like mercury and arsenic, which pose particular risks to young children and other vulnerable populations. But because shark meat is packaged and sold in Brazil under the generic name cação, rather than as tubarão, the Portuguese word for shark, Brazilians eating it tend not to know what kind of fish it is, surveys show.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Besides the risks to human health, the findings also invite questions about the extent to which government officials in charge of food and nutrition programs may be fueling the crisis engulfing the world’s sharks, whose numbers are plummeting due to overfishing.

With its own shark populations dwindling, Brazil now imports most of its shark meat, principally from Spain and Taiwan. Vessels harvest the fins, a luxury food, for Asian markets, while the much cheaper meat is absorbed by an assortment of countries, Brazil foremost among them.

Over the past several decades, shark meat, labeled as cação, has become a common sight in Brazilian grocery stores and fish markets. But the extent to which shark is being prepared for lunch and dinner in Brazilian public buildings — from food banks and fire stations to maternity wards and military bases — has not been reported until now.

“You see high levels of consumption of this food, and people are consuming it without knowing it may be harmful,” Solange Bergami, an educator in Duque de Caxias, a city in Rio de Janeiro’s metropolitan area, told Mongabay.

“What’s even more concerning is that this is not happening at a restaurant of your own choosing, where consumption is voluntary, but in a public space within an educational institution, which presumes the food provided is of good quality,” Bergami said.

Brazilian law requires online publication of government procurement records, so we spent months combing through dozens of municipal and state transparency portals to compile a long list of shark meat tenders.

The resulting data set contains 1,012 tenders totaling more than 5,400 metric tons of shark meat worth at least 112 million reais ($20 million). Issued since 2004, these tenders span 542 municipalities in 10 of Brazil’s 26 states. Only tenders with winning bidders were included in our list.

The 5,400 metric tons is unlikely to have been delivered in full, because agencies don’t always execute announced contracts. But many more shark meat tenders likely exist, as we couldn’t check every Brazilian transparency portal, and poor site functionality probably caused us to miss others. (Readers can download the tender data we compiled here, and search our list of possible shark meat recipients using a tool at the end of this article.)

*A Flourish data visualization

A separate list of federal procurements issued from 2021 to 2024, compiled by marine conservation NGO Sea Shepherd Brazil and shared exclusively with Mongabay, contains an additional 866 tenders totaling 231 metric tons of cação worth 4.8 million reais ($862,000). These tenders name dozens of universities, military bases and hospitals, among other institutions, as shark meat recipients.

More than 200 Brazilian companies appear in the municipal, state and federal data as government suppliers, offering shark meat in over 70 different brands, indicating the scope of the industry in the Latin American nation of 212 million people.

We also interviewed dozens of government officials, scientists, industry figures and ordinary Brazilians as we sought to understand the implications of the findings.

‘We don’t really know what it is’

Shark populations in the open ocean plunged by an estimated 71% from 1970 to 2018, according to a 2021 study in Nature, making them one of the world’s most threatened vertebrate groups. The IUCN classifies 16 of the 31 shark and ray species inhabiting the open ocean as critically endangered or endangered.

Shark meat traders argue sustainability concerns are overblown because the industry now relies primarily on blue sharks (Prionace glauca), amid widespread restrictions on capturing other species deemed more vulnerable to extinction. They say blue sharks, which are more fertile than other shark species, are plentiful enough that commercial fishing should be allowed.

Conservationists, though, warn that even the blue shark can only withstand so much fishing pressure. They further caution that an absence of reliable data may be masking a blue shark decline. The IUCN currently lists the species globally as near threatened.

With a global catch value of at least $411 million a year, blue shark fishing is largely unregulated, meaning vessels are often free to slaughter as many as they want even as they face strict catch quotas on tuna and swordfish and retention bans on some other shark species.

Experts who reviewed Mongabay’s tender data said that because the agencies request cação, it’s impossible to tell if they’re acquiring blue shark or a perhaps more imperiled species.

“If it’s just ‘cação,’ we don’t really know what it is,” Chris Mull, who is researching the global shark meat trade as part of a four-year project at Canada’s Dalhousie University, said by phone. “So, it’s almost impossible to say A) whether it’s legal or illegal, or B) whether it’s sustainable or unsustainable.”

DNA barcoding studies have shown that cação on sale in Brazil is often threatened species. Mislabeling is also widespread, with one species fraudulently sold as another in not just Brazil but also the U.S., the U.K., Australia and elsewhere.

“Let’s say they have to make a certain quota for a procurement and they’re like, ‘Oh, we’re a ton short,’ they could just throw in another species to make up that difference,” Mull said. “And once it’s processed, it’s very difficult to tell [what it is].”

Government officials behind the single biggest procurement we found — 600 metric tons of cação for 2,250 schools in the southern state of Paraná — told Mongabay they didn’t know what species they’d gotten.

“One of the difficulties in acquiring cação is identifying exactly what species it is, and for this reason there were environmental questions regarding this acquisition, even during the price research phase,” Angelo Marco Mortella, head of the Department of Nutrition and Food at Fundepar, Paraná’s state education agency, wrote in an email. The department only served cação in 2022 and switched to tilapia in 2023, he added.

Almost every tender in our municipal and state data asked simply for cação rather than any particular species. Procurement officials displayed more interest in the cut of the meat, frequently specifying steaks, fillets or cubes.

“It’s definitely a significant amount that’s being purchased, but a complete lack of control and visibility of how much,” Nathalie Gil, director of Sea Shepherd Brazil, said by phone. “A group of species that they should have the responsibility to protect, they’re purchasing in a way that we don’t even know if they’re selling and giving endangered species to kids.

“And if you put in the cauldron the contamination side of it, that fact that you’re giving every week a contaminated meat to children, it’s super absurd.”

We also found dozens of municipal and state purchases of peixe anjo, apparently a reference to angelshark (Squatina spp.), which is on Brazil’s endangered list, meaning its capture and trade are heavily restricted if not illegal. We’ll explore the implications of this finding in an article published in the coming days.

Pile them high and sell them cheap

Traditional shark meat consumption has a long history in some parts of Brazil. Shark can be used as the main ingredient in a seafood stew called moqueca, where it’s simmered in a base of coconut milk, tomatoes, lime and chiles.

But things have changed over the past 30 years. Shark meat has grown from niche regional cuisine to mainstream seafood, a nationwide industry comprising hundreds of companies in the capture, trade, distribution and retail sectors and — our investigation shows — propped up by tens of millions of reais in taxpayer funds.

Before the late 1990s, Brazil imported virtually no shark meat. Its own fleet caught enough to satisfy domestic demand. Brazilian fishers would haul the sharks up on deck, cut off the fins for export to Asia and then either throw the rest of the body overboard or sell the meat locally.

Monica Brick Peres, aquatic biodiversity and fisheries resources manager at Brazil’s environment ministry, remembers watching boats return to shore stuffed with severed shark fins as a child. They would target mainly hammerheads — now one of the most endangered sharks — because of the high quality of their fins, she said.

“I grew up looking at this and thinking this is unreasonable,” she said by phone.

Jettisoning the carcass after slicing off the fins, known as shark finning, enables boats to fill their limited hold space with the animal’s most valuable part, increasing profits. But the practice is also seen as cruel and wasteful, while incentivizing fishers to kill more sharks than they otherwise would.

In 1998, Peres helped lead a successful effort to make Brazil one of the first countries to ban shark finning. Under the new rules, fishers could still trade the fins, but only if they landed the rest of the shark too. Other nations followed suit.

However, some researchers believe the finning bans had the unintended side effect of creating a new supply of shark meat that had to be sold somewhere. Brazil, home to tens of millions of impoverished people, was a ready draw.

“Outside Brazil, they might have had problems selling the extra meat,” Peres said. In Brazil, “we have lots of people, and most of them are poor, and shark meat is cheap. … People want to give some protein to their children.”

An anti-hunger campaign initiated by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva seeded additional demand. One of the first Lula administration’s major acts (he held office 2003-11 and was reelected in 2022) was to enact a universal right to free school meals for every student in public primary school. He also promoted fish more generally as a healthy alternative to ultra-processed food. From 2003 to 2009, Brazilian fish consumption rose by 40%, to 9 kilograms (20 pounds) per person annually.

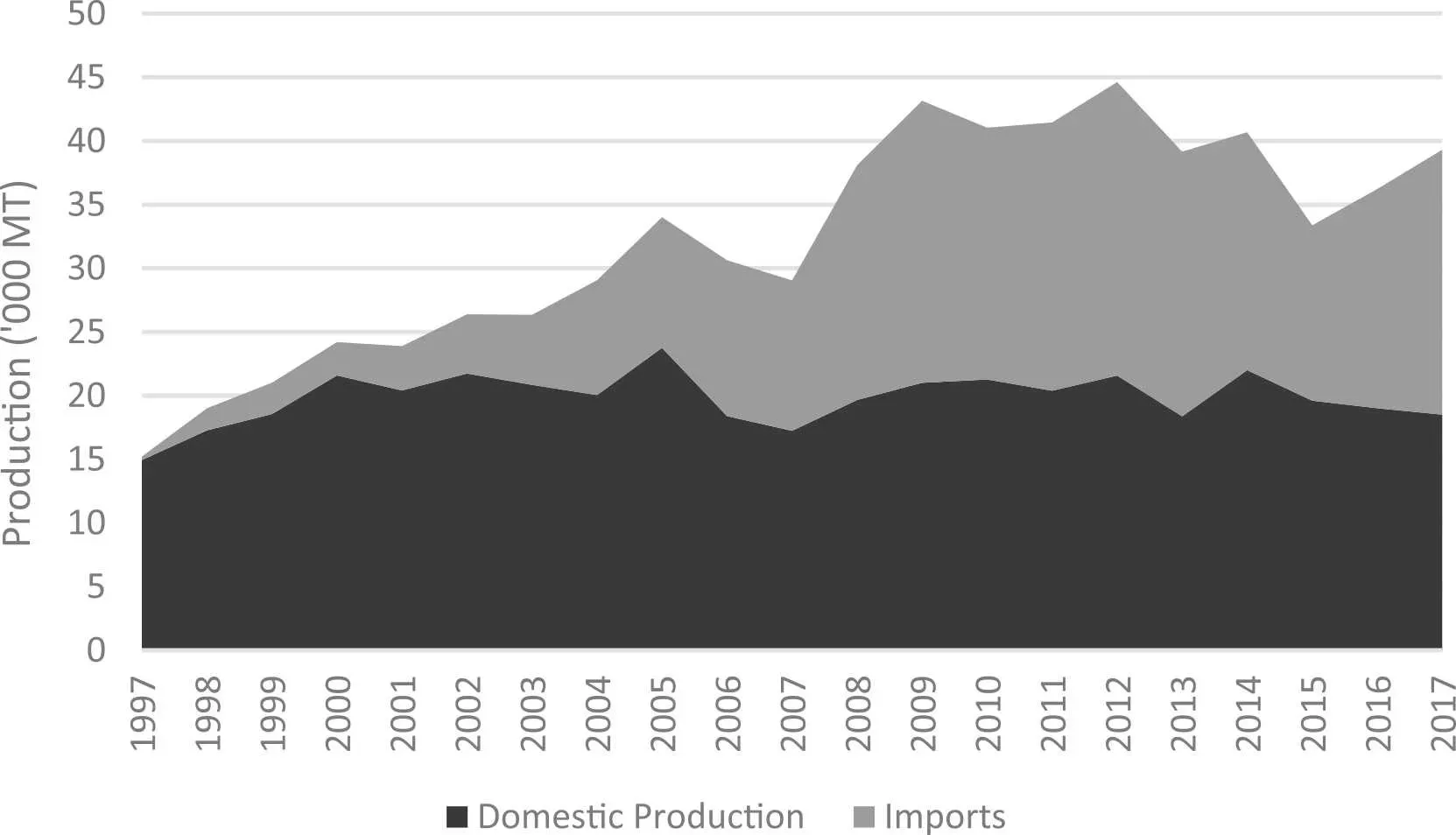

Brazil’s shark meat imports mirrored these trends, creeping up from near zero in the mid-1990s to 2,500 metric tons at the turn of the century, before skyrocketing past 20,000 metric tons per year in the 2000s. Brazil’s own shark catch stayed relatively constant during the same period, at around 15,000-20,000 metric tons annually.

Brazilians’ lack of familiarity with fish in general made them less likely to turn up their noses at shark meat, which is generally seen as low-grade, according to Martin Dias, scientific director for the NGO Oceana’s office in Brazil.

“We never had a focus on fish — our best fish are exported,” Dias said by phone. “But then that cheap meat, left over in a country that doesn’t have much of a culture of eating higher-quality fish, etc., that started to come in. And we began to consume it.”

It was only a matter of time before the affordable, readily available shark protein found its way into school meals, according to Rodrigo Agostinho, the head of IBAMA, a regulatory and enforcement arm of Brazil’s environment ministry.

“At some point, [the nutritionists] decided to recommend it to everyone,” said Agostinho, who signed off on several shark meat procurements while serving as mayor of Bauru, a city in São Paulo state, in the mid-2010s. “‘Look, for school meals, to avoid problems with children choking on bones, buy this type of meat.’ There was a decision, and a culture was created in Brazil.”

Bone appétit

Bergami, the Duque de Caxias educator, began trying to get shark meat removed from school meals in the city around 2021, when she noticed students complaining about the taste and smell and refusing to eat it.

Sharks have skeletons made of cartilage, making them easier to process and prepare than bony fish. But their blood and tissues are also high in urea, which can decompose into pungent ammonia if the carcass isn’t properly handled. “The meat will smell like a public restroom,” Eduardo Bessa, a biology professor at the University of Brasília, told Mongabay on campus.

Bergami said she believed in the feeding program’s mission of instilling kids with healthy eating habits and hated to see them scraping their main courses into the trash. “Our students are from less-privileged backgrounds, so they don’t have this culture of eating fish, or proteins in general, like meat, chicken, beef,” she said in an interview. “So, for us it’s also very important that fish is on the menu.”

It was only when she did some research that she learned cação was shark — and about the health risks from metal and metalloid contaminants. Exposure to these elements can harm human health in a variety of ways, from damage to organs like the brain and kidneys to increased risk of cancer and other diseases, according to a wide body of scientific literature.

As president of the city’s school feeding council, which monitors school meal quality and compliance, Bergami asked the municipal education department to replace cação with a different fish. But she said they told her it couldn’t be done.

“The nutritionist claimed it was the fish with the least bones,” Bergami said. “There was no new bidding process and the fish — the cação — kept being served.”

Brazilian government agencies employ thousands of nutritionists who draw up the meal plans that food procurements are based on. These nutritionists often favor cação because of the lack of bones, sources told Mongabay.

“Just imagine a child in day care, or even an older child, choking on bones — it’s a situation no colleague wants to go through,” Jeanice de Azevedo Aguiar, an adviser to the Regional Council of Nutritionists — 3rd Region (CRN-3), which oversees the São Paulo and Mato Grosso do Sul states, said in a video call. “Depending on the severity of the choking, the child might have to be hospitalized.”

Buyer agencies echoed that sentiment. Colegio Pedro II, a federal public school with 12,000 students, told Mongabay that it served cação “above all” because it has no bones. The Foundation for Childhood and Adolescence, a Rio de Janeiro state body, said it had chosen to serve cação at a group home for disabled youth because the lack of bones made it “easier to chew and reduces the risk of choking, which is crucial for patients with motor and intellectual disabilities.”

Agostinho, the Bauru mayor turned IBAMA chief, said he’d faced “enormous resistance” from government nutritionists when he’d tried to question the city’s procurement of not just shark but also ray meat, which was purchased several times for schools under his watch from 2013 to 2016, documents show.

“The procurement processes only reach the mayor for signature once everything is already done,” Agostinho told us at his office in Brasilía. “You try to say no, and the nutritionist responds, ‘So it’s the mayor who decides what I’m going to serve the children?’ … They would say, ‘No, you can’t put children’s lives at risk.’ … ‘I’m going to give children meat that doesn’t have bones,’ as if it’s not safe otherwise.”

Price was also a factor, he said, because buying a more expensive product when a cheaper one is available could invite scrutiny from government auditors.

Don’t you know that you’re toxic?

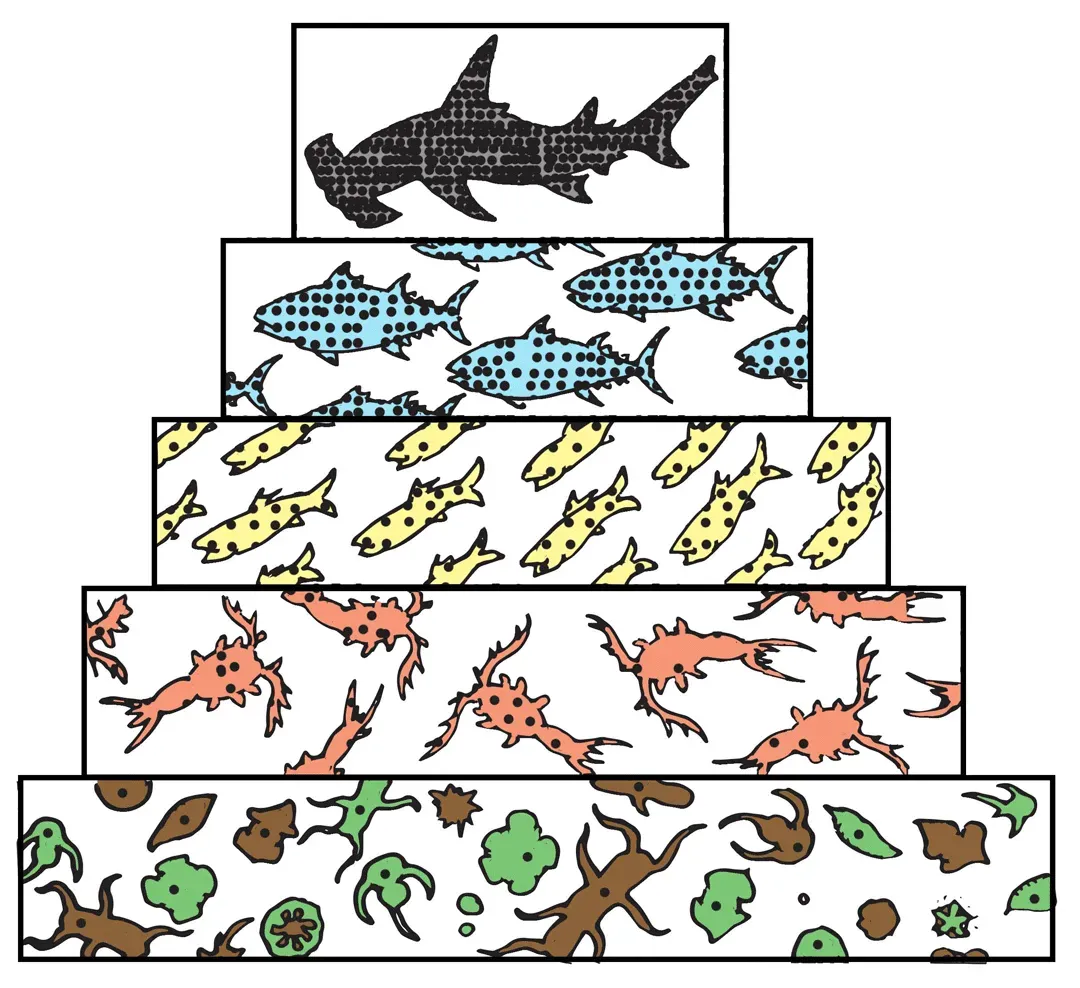

While bonelessness is a selling point, sharks are also high in contaminants such as mercury due to a process called bioaccumulation. That’s when one animal eats other animals, which themselves have eaten other animals, and so on, with certain chemicals absorbed by all of them throughout their lifetimes accumulating in the predators at the top of the food chain.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Brazilian health regulator ANVISA both set limits for mercury in shark meat at 1 milligram per kilogram, matching World Health Organization guidelines, above which the product can be recalled.

But while the FDA warns adults to eat shark meat only sparingly, and young children and pregnant and nursing mothers to avoid it entirely, Brazil’s Ministry of Health actually recommends cação for toddlers and infants. The ministry’s feeding guide for children under 2 highlights the lack of bones but makes no mention of contaminants.

Contaminant loads can vary greatly among individual sharks due to factors like species and habitat. An FDA monitoring program found that mercury levels in 356 sharks averaged just less than 1 mg/kg but ranged as high as 4.5 mg/kg. Similarly, a study of tissue samples of 27 blue sharks caught off the coast of Brazil found that 40% exceeded 1 mg/kg.

Brazilian procurement rules allow agencies to request lab testing for heavy metals, but it’s not required. Only a tiny handful of tenders reviewed by Mongabay explicitly called for such tests.

Heavy metals testing “may be done by federal or state laboratories — but routine testing is not always performed,” Rachel Hauser-Davis, a British environmental researcher based at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, known as Fiocruz, a research institute affiliated with Brazil’s health ministry, wrote in a message.

Shark traders tend to downplay contamination concerns. Spain’s Interfish, which represents shark and swordfish interests, says on its website that “there is no risk of mercury toxicity thanks to the selenium present in these fish, a key element that neutralizes mercury, making seafood safe and healthy to consume.”

Hauser-Davis called that claim “very irresponsible, as it leads to people believing that selenium can 100% ameliorate mercury effects.” Selenium “does have a protective effect against mercury, but this depends on HOW MUCH mercury there is in a certain foodstuff (fish, meat, etc), so the protective effect is NOT ALWAYS TRUE.”

Mercury isn’t the only contaminant found in shark meat. Arsenic was “generally the most prevalent element detected” in a number of studies on metal contamination in sharks, according to a 2024 paper Hauser-Davis co-authored, with blue sharks among those showing high levels. Both elements, along with cadmium, another toxic heavy metal, frequently surpassed safety thresholds established by regulators, the studies found.

For members of the general population, any ill effects arising from exposure to these contaminants tend to appear after the better part of a lifetime, according to Patricia Charvet, biology professor and visiting researcher at the Federal University of Ceará and regional vice-chair of the Shark Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission.

“It’s not the kind of thing you eat once and you get sick — usually, it’s cumulative,” she said by phone. “So, for the generations now that are consuming a lot of shark meat, the problems are going to appear further down the line. They’re going to appear when they’re over 50, over 60 or more, because we tend to build contaminants in our fatty tissues.”

For vulnerable groups such as young children, the elderly and the immunocompromised, the risks can be more immediate, Charvet said. “The situation is even more concerning if shark meat is being consumed by pregnant, nursing mothers, infants and toddlers since contaminants can lead to neurodevelopmental problems in a much shorter timeframe,” she wrote in an email.

That hundreds of Brazilian day cares and preschools were apparently serving shark meat to the very young is “scary from the point of view of potentially causing serious problems,” she said.

A 2023 tender to feed the 43,000-strong Rio de Janeiro state military police corps for a year specified that each officer was supposed to eat 3 kg (6.6 lbs) of cação per month. A 2024 tender set the amount at 2.3 kg (5 lbs) per month.

“Mother of God!” Aguiar, the nutritionist council adviser, exclaimed upon hearing those figures. Charvet called the figures “alarming” and pointed out that any government employee, military staff or prisoner who fell ill from contaminant exposure would rely on the same public health system for treatment that fed them shark in the first place. The state military police did not respond to a request for comment.

Brazilian university students pursuing a nutrition degree typically don’t learn about toxicology, sources said.

Judith Gomes de Oliveira, a nutritionist who’s coordinated the menu for the university restaurant at the Federal University of Ouro Preto for 30 years, didn’t even know cação was shark until Mongabay requested an interview, although the restaurant previously served cação. “Maybe if I’d studied oceanography, I would have known,” she joked.

Last year, the Duque de Caxias school feeding council under Bergami escalated its complaint to the Rio de Janeiro state nutritionists council, CRN-4. Since then, she said, the city had suggested it would stop serving shark, but when we met Bergami in April, cação was still being served. This week, she told us that was still the case at nearly 200 public schools in the city.

The Duque de Caxias city hall told us in an email that it was conducting acceptability tests with other types of fish to replace cação, but were encountering issues with bones. “Our children are a priority, and we strive to provide a healthy, varied diet,” they said.

Tatiane Amorim Mello de Matos, a mother with three children in Duque de Caxias public schools who represents parents on the city’s school feeding council, said she believed the officials serving her kids shark were probably unaware of the health and environmental issues.

“When we don’t have the knowledge, that’s one thing,” Matos said in an interview. “But from the moment we do, and they still don’t do anything, that’s when we know how to hold them accountable and in what way, because they won’t be able to claim ignorance anymore.

“When someone says, ‘Oh, I didn’t know,’ I’ll be the first to say, ‘No, but I do.’ I know that cação meat is shark meat, and as a mother, I don’t want that served in my child’s school.”

Culture at a crossroads

In a few scattered instances, civil society pushback has resulted in policy change. Most prominently, the city of São Paulo canceled a 650-metric-ton shark meat tender for school meals in 2021 after conservationists objected and one of Brazil’s biggest TV news channels covered the story.

Images from video "Compra de cação para merenda escolar em SP provoca polêmica por riscos à saúde" by Fala Brasil, follows.

That same year, Santos, also in São Paulo state, became Brazil’s first municipality to ban shark meat from school meals, citing environmental and health concerns. And Paraná state mandated that any cação product carry the species name after a survey of shoppers there showed that most who had eaten it didn’t know it was shark.

Those cases aside, shark meat procurements remain widespread. Some 290 tenders in our municipal and state data were issued between 2022 and the present.

In the four biggest cities in the southeastern state of Espírito Santo, for example — Vitória, Vila Velha, Serra and Cariacica — we found 20 tenders seeking a combined total of 463 metric tons of cação issued since 2022. In Salvador, a major northeastern city, we found three tenders requesting 132 tons since 2021. Mongabay identified a number of open tenders for 2025 cação supply contracts.

Sea Shepherd Brazil is calling for a ban on all institutional purchases of shark meat. The group supports a bill authored by Nilto Tatto, leader of the environmental caucus in Brazil’s lower house of Congress, that would prohibit shark meat procurements by federal institutions, now making its way through the committee process.

In the meantime, Sea Shepherd is working to increase consumer awareness. Its “Cação é Tubarão” campaign seeks to spread the word that Brazilians’ favorite cheap fish is actually shark. It came as a surprise to several sources Mongabay consulted for this story.

“I bought, cooked, and ate cação my whole life without having any idea it was shark meat,” Laura Oliveira, an early childhood educator who grew up in São Paulo, told Mongabay. “It’s not something that people are made aware of.”

Vitor Hugo do Amaral Ferreira, director of Brazil’s Consumer Protection and Defense Department, also didn’t know cação was shark until we contacted him. “I’m not going to say there’s consumer fraud going on here, but there’s information that’s not clear, not precise and not explicit,” he said at his office in Brasília. “[Consumers] must at least have the knowledge so they can make an informed choice, what this cação is, right?”

Brazil’s Federal Council of Nutritionists, a federal agency, acknowledged that the term cação can be misleading, writing in an email that its use “can mask the commercialization of endangered or unsustainably caught species.” It therefore emphasizes “the importance of accurate labeling: identifying the species with its scientific and popular name.”

Mull, the Dalhousie University researcher, said the procurement data disclosed in this article could bolster efforts to enhance traceability in shark supply chains. Companies identified as leading suppliers, he said, would be logical focal points for enforcing rules set by CITES, the global convention on trade in endangered species, which restricts trade of more than 100 shark species.

“Those might be companies for [the authorities] to check out, like using DNA barcoding technology or something to try and identify what the species composition is coming in,” he said.

Ayrton Assumpção Troina, founder of A3T Group, an import-export firm based in Santa Catarina state, said he welcomed regulation but argued the shark meat trade must be allowed to persist due to its economic importance.

“There are many people involved, many people working, many taxes generated,” he said by phone. “It cannot be treated as a marginal activity.”

Agostinho, the mayor turned IBAMA chief, said he would support a moratorium on cação procurements until shark populations showed signs of recovery. Either way, he said, the federal government must issue a coherent policy on shark meat, before it’s too late.

“We need to change this culture,” he said. “Not because shark or ray meat should never be consumed, but because their stocks are critically low.”

Jacobson reported from São Paulo, Santa Catarina and Rio Grande Do Sul; Mendes reported from Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais and Brasilía.

- View this story on Folha De S. Paulo

(1).jpg.webp?itok=DKf4X01l)