Over the past decade, the military-aligned warlord and his associates amassed wealth from Kachin State’s rare earth mining boom until the Kachin Independence Army took their territory last year, but that hasn’t prevented them from continuing to do business.

On March 31, three days after a devastating earthquake hit central Myanmar, a strange photo appeared on Facebook. It shows a man in jeans and a polo shirt handing a paper box labelled K100 million (about US$23,000 at the market rate) to a man in traditional formal attire. A screen behind them announces an earthquake relief donation ceremony in the Kachin State capital Myitkyina, and the room’s decor indicates an official building.

The man offering the donation is Zahkung Ying Sau, a politician with the New Democracy Party-Kachin and son of Zahkung Ting Ying, one of Kachin’s most prominent warlords. The recipient is Hkyet Htingnan, the regime’s chief minister of Kachin.

The photo appeared on the Facebook page Kachin SR-1. Describing itself as a news and media company in Kachin’s Chipwi Township, it is one of several pages created in recent months with content related to the state’s former Special Region 1. This territory was controlled by armed groups affiliated with Zahkung Ting Ying for more than three decades, during which he and his allies leveraged their ties to the military and cross-border networks with China to engage in a range of businesses, largely illicit.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

In recent years, they became kingpins of a lucrative rare earth mining boom, capitalising on surging global demand for elements used in the production of electric vehicles, wind turbines and military weapons. That came at a time when China, the world’s largest rare earths processor, was looking for new places to source them.

The 2021 military coup brought new levels of impunity to those doing illicit business in Myanmar, and rare earth mining intensified. Then in October last year, the Kachin Independence Army, which has taken a leading role in the post coup resistance against the regime, seized the territory’s headquarters of Pangwa town, in Chipwi. Zahkung Ting Ying was rumoured to have fled to China; not long after, his Border Guard Force and an affiliated militia were effectively defeated and the KIA’s political wing, the Kachin Independence Organization, began administering the territory.

More than nine months later, Zahkung Ting Ying and his associates remain without territory. The earthquake donation ceremony, however, is one of several indications that the tycoons of Kachin Special Region 1 are using their political and social networks to keep their business interests afloat.

“The show is not finished. They still have some scripts to play,” said a Kachin political analyst, speaking on condition of anonymity due to security concerns. “Their future depends a bit on how the Myanmar Spring Revolution will end.”

Central to this story is Zahkung Ting Ying, from Kachin’s ethnic Ngochan minority. A commander with the KIA during its early years, he broke away in 1968 and joined the Communist Party of Burma. When the CPB collapsed in 1989, he established the New Democratic Army-Kachin. The NDA-K signed a ceasefire with the military the same year, and was given effective autonomy over territory along the border with China’s Yunnan province.

Over the following two decades, the mountainous Special Region 1 became a hub for poppy cultivation and logging. In 2009, the NDA-K came under the military’s nominal command as a Border Guard Force. As the opium and logging trades waned, rare earth mining expanded, particularly around the town of Pangwa.

Along with the mining came dramatic changes in the landscape, as companies cleared mountains, injected toxic extractants, and precipitated the rare earths in large chemical pools. In recent years, the environmental damage and the health and safety risks posed by the mining have been increasingly exposed. So far, however, the people and companies behind the industry remain largely hidden.

This investigation seeks to uncover these networks, revealing how a small group of people have profited from rare earth mining in Kachin and established a web of commercial enterprises which affords them the ability to launder the proceeds. It focuses on local business networks, in a region where armed groups and their associates have long partnered with Chinese investors to profit from extractive industries.

This investigation was conducted in collaboration with the activist group Justice For Myanmar. In addition, Myanmar Witness, a project run by the Centre for Information Resilience, provided open source data and satellite imagery analysis, as well as investigative support.

‘No one is doing checks and balances’

Rare earth mining in Myanmar emerged in the early 2010s but took off during the term of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy beginning in 2016. The civilian government inherited a mining sector characterised by opacity and conflicts of interest, often involving the military and its affiliates.

The NLD took some steps to strengthen regulation over the sector, in partnership with civil society groups and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, an international nonprofit. One of its most ambitious efforts was to push companies to disclose their beneficial owners and shareholders. The initiative largely failed, however, and the NLD was criticised for not achieving meaningful reform.

“The whole extractive sector was corrupted,” said a civil society worker who focuses on natural resource governance reform, speaking on condition of anonymity. “There [was] a system on paper … It’s a fake system. There’s another system behind the scenes.”

Kachin Special Region 1’s remoteness and semi-autonomous status brought an added layer of impunity over the rare earth mining industry, sources said. Several suggested that the BGF had its own system of permits outside of that managed by the NLD government.

According to the civil society worker, Zahkung Ting Ying’s groups also controlled who could enter Kachin Special Region 1, and what they could see and do. “[If] you are asking about transparency and accountability, it is very far,” he said. “It is almost irrelevant.”

Then the coup happened, and Myanmar’s civic space contracted. According to the civil society worker, any prospects of holding people and groups to account for their business practices in Kachin’s rare earth mining industry disappeared. “No one is doing checks and balances,” he said. “Even though reports come out about rare earth mining, [those involved] don’t give a s***, and we can’t do anything.”

A 'criminal business empire'

These factors make the Kachin BGF’s business networks difficult to trace. Still, by piecing together interviews, online research and corporate records, some details can be established.

Sources who have lived, worked or done research in the Pangwa area said that the chairman of Kachin Special Region 1, Zahkung Ting Ying held ultimate authority over the territory, but that as he grew older, his children – daughter Ying Myaw and sons Ying Sau, Ying Chan and Ying Ting – increasingly managed the family’s businesses.

In total, they are listed as the directors of at least 29 companies in Myanmar, including those whose licences are now expired, according to corporate records accessed through the free international database OpenCorporates, a commercial risk intelligence provider, and JFM. These companies include tour agencies, hotels, gem and jewellery businesses, as well as companies involved in transportation, construction, mining and development.

Only one company linked to the family through corporate records – Myanmar Myo Ko Ko Medical Instrument Company Limited – could be traced to rare earth mining by official permits. This permit data is not publicly accessible, but a copy sent to Frontier by an NGO source shows the company had permits to mine rare earths over five plots in Chipwi Township, totalling 135 acres, for six months beginning in November 2018.

The military has not published mining permit data since the coup, making it difficult to confirm whether it allowed Myanmar Myo Ko Ko or other companies to mine rare earths. But civil society and activist sources who have done research on rare earth mining in Kachin named three companies or company groups in Zahkung Ting Ying’s network – Myanmar Myo Ko Ko, Chang Yin Khu and San Lin – which they said were involved in the industry.

Frontier was unable to independently verify claims about Chang Yin Khu – a group of five companies affiliated with Zahkung Ting Ying – or San Lin, for which corporate records show a San Lin International Export and Import Company Limited also affiliated with the family.

A labourer, however, described working on a Myanmar Myo Ko Ko site for around six months last year. A photograph he sent to Frontier shows chemical leaching pools characteristic of the rare earths industry. Local media outlets also reported a deadly landslide on a Myanmar Myo Ko Ko rare earth mining site in the Pangwa area on June 4 last year.

Frontier sent emails to Myanmar Myo Ko Ko, as well as San Lin and Chang Yin Khu, but did not receive a reply.

According to JFM, the ability of Zahkung Ting Ying and his circle to amass fortunes through rare earths is tied closely to their alliance with the military. “Zahkung Ting Ying built a criminal business empire that has caused mass devastation to communities and the environment, while channeling dirty money from illegal mining to his family and other partners in crime,” said JFM spokesperson Yadanar Maung. “This has only been possible with the complicity of … Myanmar military commanders.”

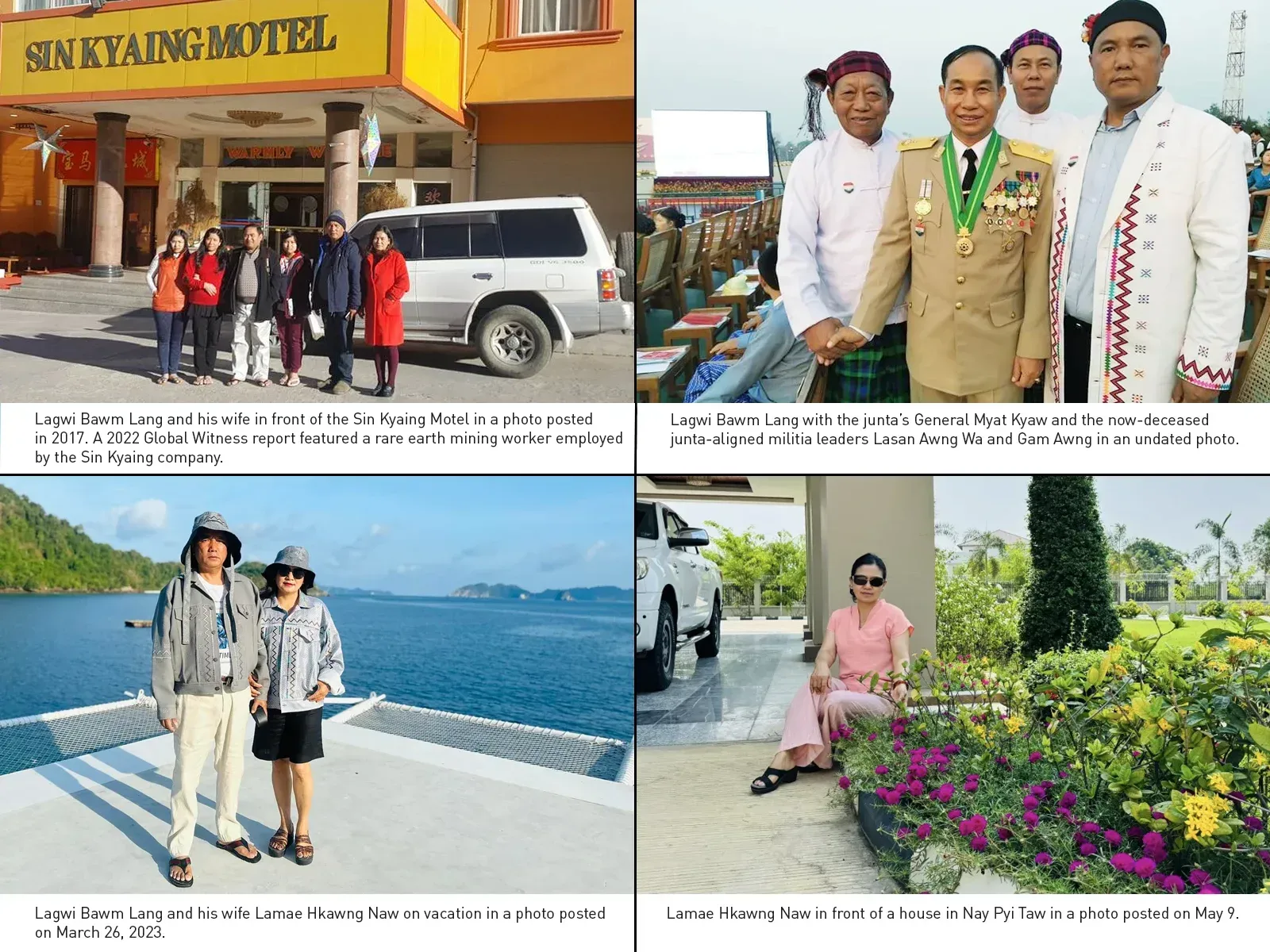

While Zahkung Ting Ying was the most prominent person in Kachin Special Region 1, he was not the only warlord in the territory. Sources also named Lagwi Bawm Lang, who headed a militia aligned with Zahkung Ting Ying’s BGF, as a key figure in the rare earth mining industry.

A native of Muse town, in northern Shan State, Lagwi Bawm Lang belongs to the Lachid ethnic group which makes up a major proportion of the population in the Pangwa area. His rise to power began around 2013, when Zahkung Ting Ying appointed him to lead a militia in the area, according to local sources. They said that over the following decade, Lagwi Bawm Lang established himself as one of the most influential people in Pangwa.

Corporate records show him listed as a director of at least 12 companies in Myanmar including some with expired licences. These companies’ activities include mining, infrastructure and logistics. Civil society and activist sources named two of these companies – San Lin and Bawm Myang – as involved in rare earth mining in Pangwa.

Frontier was unable to independently confirm these claims, and neither company replied to emailed requests for comment. But a report published by the environmental watchdog Global Witness in 2022 quotes a rare earth mining labourer employed by another company affiliated with Lagwi Bawm Lang, the Sin Kyaing company, alongside photos of a rare earth mining site. This company also did not reply to an emailed request for comment.

The Kachin BGF’s network also extends to the junta, where the current Kachin State minister of natural resources and environmental conservation is Mangshang Ting Sau. An ethnic Lachid from Mong Ko town, in northern Shan’s Muse Township, he previously served as a commander in Zahkung Ting Ying’s NDA-K, according to Myanmar Now. He was elected to the upper house of parliament in 2015, and in the lead-up to Myanmar’s general elections in 2020, served as the chairman of the New Democratic Party-Kachin, for which Zahkung Ting Ying was the patron.

Corporate records show Mangshang Ting Sau listed alongside Lagwi Bawm Lang as a director of the Bawm Myang company and five companies with Sin Kyaing in their names. In March 2022, Mangshang Ting Sau led a monitoring visit to rare earth mining sites in the Pangwa area through his role in the Kachin State regime administration.

According to JFM, Mangshang Ting Sau helps to ensure that profits from Kachin’s natural resources flow to the military and its affiliates. “His position in the military junta further demonstrates the intertwined interests of Zahkung Ting Ying’s network with the Myanmar military, as well as the junta’s systemic corruption,” said Yadanar Maung.

A mining magnate, a celebrity and a shopping centre

Another prominent businessperson with ties to Zahkung Ting Ying is Mangshang Ding Ying. An ethnic Lachid, he headed the NDA-K’s economics department in the 1990s and early 2000s and then left the organisation, according to multiple sources. “Mangshang Ding Ying was a good mediator or had some kind of good relationship with the military,” said a source who knew him at the time, describing him as “the most trusted” in Zakung Ting Ying’s circle and “the one who dealt with the Chinese businessmen”.

In 2004, Mangshang Ding Ying jointly registered a Myanmar Apex (Pang Wah) Mining Company Limited with Zahkung Ying Sau, Zahkung Ting Ying’s wife and a fourth person named Saw Naing, corporate records show. Myanmar mining permit data accessed by an NGO source indicates that the company had three permits to mine lead and tin in the Pangwa area from 2015 to 2020.

Myanmar Apex formally dissolved in 2020, but Ding Ying has two live companies in Singapore –Myanmar Apex (Pang Wah) Mining Pte Limited and Panwa Resources Pte Ltd – which appear to be connected to the same network. A fourth company, Panwa Resources Pte (USA) Limited, was registered in California in 2018; its business licence was suspended in 2022.

These companies are just a small part of Mangshang Ding Ying’s vast business network. His Developers Entrepreneurs Liaison Construction Organizers Limited Company, established in 2007, claims on its website to be the largest mining, mineral processing and metallurgical company in Myanmar, specialising in tin-tungsten and mixed ores.

Multiple sources familiar with local business networks who were interviewed for this investigation suggested that although Mangshang Ding Ying cut formal ties with Zahkung Ting Ying’s groups, he may still be benefiting from connections established during his time in the NDA-K. Some of these sources also suspected Mangshang Ding Ying was still doing business in Kachin Special Region 1 up until the KIA takeover last year; while none were able to prove his connection to rare earth mining, they suggested that his profile and networks were likely to afford him unique access to the industry.

Frontier emailed a list of questions to Mangshang Ding Ying through the address provided on the website of his company, DELCO, but did not receive a reply.

This investigation also identified two additional people of significance with likely connections to Kachin’s rare earth mining industry which have not previously been reported. Both are named Jung Zang Dau Lum. One is a celebrity film producer, director, actor and singer who goes by JZ Dau Lum. The other served in Zahkung Ting Ying’s BGF until the KIA takeover last year, according to multiple sources. They said that the two men, both from Kachin’s ethnic Lhaovo community, are relatives of each other who jointly profited from rare earth mining through a company called Ginlum.

Corporate records show a Gin “Lheim” company registered in Yangon in 2015 with four directors. By cross-checking this list with public social media posts and interviews, Frontier identified the directors as JZ Dau Lum; his wife Su Mon Hla Aung, who goes by Zung Mai; Zaw Tun Oo, a businessman who is also connected to JZ Dau Lum through MK Media, a film production studio and online channel; and Larae Ze Naw, the wife of Dau Lum of the BGF.

One labourer described working on a Ginlum rare earth mining site until it shut down last year for unknown reasons. Photos he took in May 2023 show chemical pipes and leaching pools.

A Ginlum company associated with JZ Dau Lum was also responsible for the construction of a luxury shopping complex in Myitkyina, according to a post on the regime’s Kachin State government website. The complex, called the JZ Centre, celebrated its grand opening in March. It now includes the JZ Bar and Restaurant, JZ Luxury Cinema, JZ Food Corner, and retailers selling gems and jewellery, textiles and mobile phones.

Frontier contacted the Gin Lheim company and JZ Centre by email, but did not receive a reply.

Meanwhile, sources familiar with the context said that even though Zahkung Ting Ying is without territory, he and his close associates are continuing to do business, and are likely to be reinvesting in industries including gold mining, petroleum and hotels, while negotiating deals for a share of the rare earth wealth. Frontier was unable to independently confirm this information, but public social media posts analysed by the authors of this report in collaboration with Myanmar Witness indicate that the Zahkung and Lagwi families have been travelling and developing their networks since their defeat to the KIA.

Zahkung Ting Ying’s son Ying Sau has also posted video clips on Facebook, one claiming to show a jungle military training camp, and another with the caption “marching towards the Special Region”. On July 31, the junta announced a state of emergency over five Kachin townships including Chipwi, indicating a possible return to conflict in the area.

JFM called on international actors to do more to stop the illicit flow of funds to Zahkung Ting Ying and his networks. “While the Kachin BGF has been defeated in battle, the business empire still needs to be fully dismantled,” said Yadanar Maung. “The Kachin BGF’s business network should be targeted for sanctions, Zahkung Ting Ying and his associates must be held accountable for their crimes, stolen assets need to be recovered and their victims must be compensated.”

Zau contributed to this report.